This article was produced through the Environmental Justice Oral History Project, a digital hub that combines oral history, student journalism, podcasting, events, and research to document culture and environmental racism in the U.S. South.

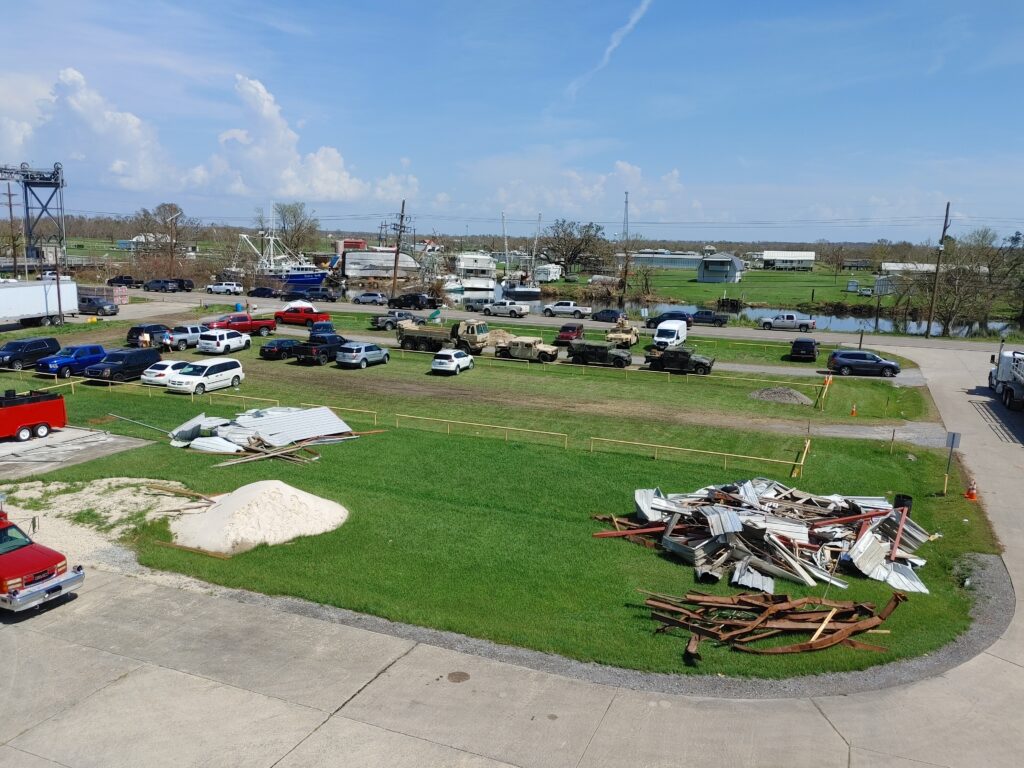

As Hurricane Ida ripped through the small bayou city of Chauvin, Louisiana on August 26, 2021, Category 4 winds pulled at trees, tossed around a haze of water, and shifted loose items on the ground. In one sudden moment amid the storm, a large piece of debris—a roof from a nearby shed—went flying across the backyard of one of the city's fire stations and into the top right corner of the building, ripping the station's roof off.

"It hit the door on the whole back of the building and it just—BOOM!" said Marty Thibodeaux, the then-chief of Chauvin's Little Caillou Volunteer Fire Department. "It was like a train ran into the station."

Thibodeaux, now retired, said that overall, Ida's wrath caused about $100,000 worth of damage to the headquarters station located on Highway 56. Repairs to the station have been completed. But other stations that were fully destroyed during Ida have yet to be repaired, and the Chauvin community—like the rest of Terrebonne Parish—remains a different world than it was before Ida.

What Storms Sow

Ultimately, Hurricane Ida claimed 26 lives in Louisiana. Subsequent flash flooding on the East Coast killed an estimated 50 more people, and the storm is believed to have cost a total of $75 billion in damages. What's more, the damage of Ida—as with all major storms—extends beyond the immediate aftermath. For any disaster-stricken community, their plight does not end when storm winds die, floodwaters recede, and fires are extinguished. Rather, a bevy of subsequent problems emerge, and a community may never be the same again.

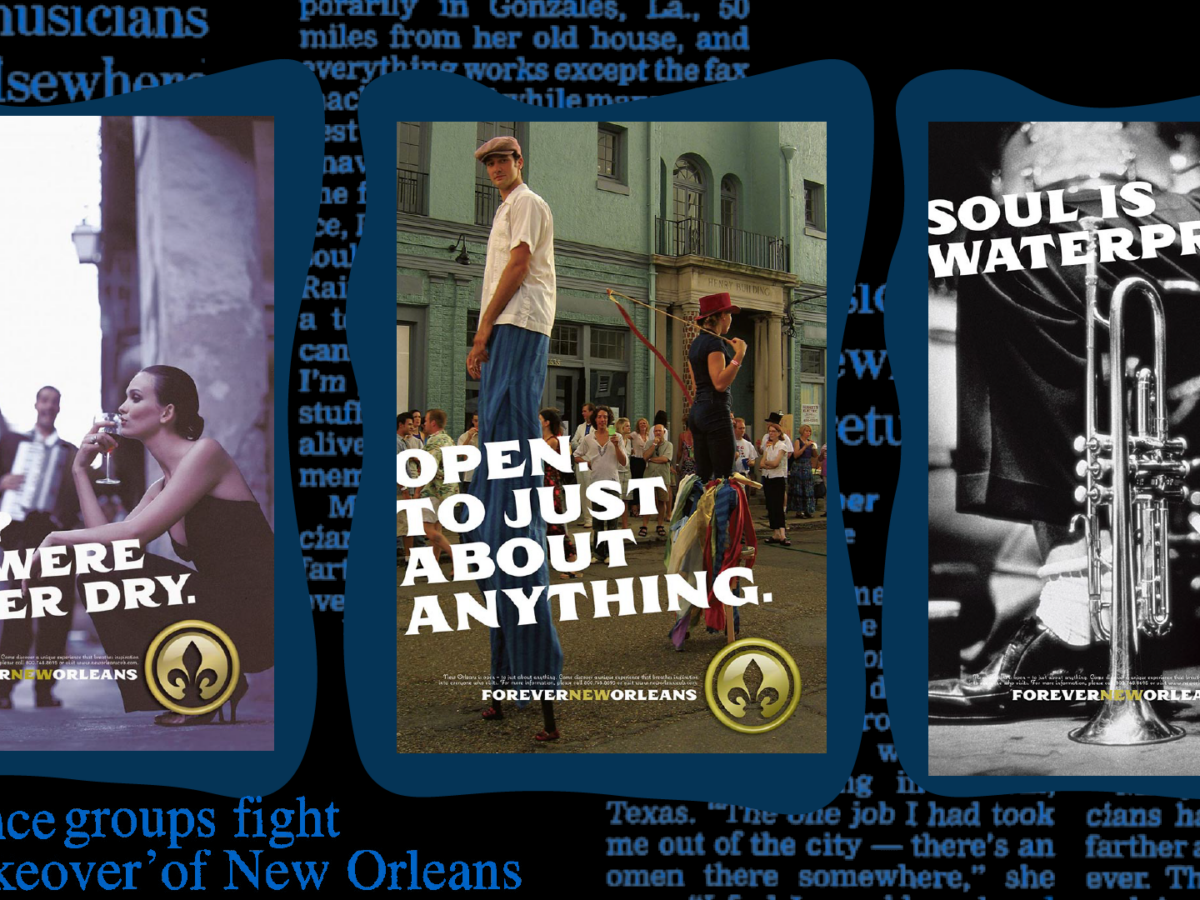

One such problem: swiftly after disaster events, insurance price hikes and land poaching commonly unfold in storm-swept areas. For example, according to a 2023 study published in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, home prices in disaster-impacted areas in Florida increased an average of five percent within three years after hurricanes–with a peak increase of 10 percent occurring in the second post-storm year. According to a 2006 NBC article, in the first quarter of that year—just months after Hurricane Katrina—the sales total of single-family homes in greater New Orleans was 60 percent higher than the sales total of the first quarter of 2005, with 960 more units sold in the 2006 period than in the 2005 period.

These price hikes and buying frenzies upend housing markets, harming residents' abilities to repair or rebuild their ruined homes. Additionally, local services and infrastructure may suffer reduced capacity due to resource losses or facility damage. Such consequences of a disaster mark a reshaping of the very DNA of a community—and at the core of this destruction is disaster gentrification.

What is Disaster Gentrification?

Disaster gentrification is a hybrid of different forms of geographical displacement: disaster displacement, direct gentrification, and indirect gentrification, according to Jessica Simms, program officer of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine's Gulf Research program.

Low-income residents are forced to leave their community because they can't financially rebuild after a disaster or are forced to rebuild according to difficult-to-manage government codes set on the grounds of future weather resilience, something that most Black, Indigenous, and/or low-income residents can't build due to continually having to bear the brunt of climate disasters and extreme weather events. Simultaneously, wealthy corporations or upper-class individuals—most often white or white-led—move into the vacated spaces because those buyers can afford to "appropriately" build or rebuild in a disaster area. This market influx cements the home and insurance cost hikes, pricing out longtime residents and transforming communities into white neighborhoods with shifts in commercial landscapes.

A recent example of disaster gentrification unfolded when devastating fires swept Maui in early August 2023. Post-disaster land grabs occurred very swiftly and publicly. In that case, the land grabs were largely denounced by the public.

However, the Hawaii situation is far from the first or only example of disaster gentrification in the U.S. Thousands of miles away from Maui lies Louisiana, the state that's home to two of the most infamous examples of disaster gentrification: what happened in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and the relocation of the Indigenous people of Isle de Jean Charles, a process that began in 2016.

Disaster Gentrification: Louisiana's Legacies

When Adrinnie Duchane, a short-haired, bespectacled, 41-year-old Black woman—whose warm energy cuts through the silence of a morning Lyft ride in May—thinks about New Orleans, she thinks of love, family, friends, and culture. At least, she says, that's what her hometown was full of before Hurricane Katrina.

"E'rrybody was here. [You had] auntie on one block, cousin on anotha block, auntie and grandma around the corner," said Duchane, from behind the wheel of her car as she navigated New Orleans traffic. "But now, it's like everything's displaced. Your community is not like what your community…used to be."

When Katrina hit the U.S. in August 2015, it became the single costliest storm and one of the five deadliest in U.S. history—with 1,833 fatalities and about $108 billion in damages (in 2005 dollar value), according to the National Weather Service.

Duchane, who was 23 years old at the time and a native of New Orleans' Ninth Ward, said her community lost many people that day. They were either killed by the storm or forced to move away permanently. With that loss, the community underwent a marked decline in the connectivity of its people.

Even as the city has seemingly recovered in the decades since, with tourism currently significantly trending upward, longtime residents feel excluded from such progress and unsupported by the city government. For example, Duchane points to the abundance of abandoned homes that sit between new businesses throughout the buzzing city.

"I love my city, but at the same time, it's broken," said Duchane, who has twice moved out of New Orleans but returned around 2019. "New Orleans to me now is totally different."

Such death of community is familiar to people living about 80 miles south of New Orleans, in Terrebonne Parish's bayou island Isle de Jean Charles.

Isle de Jean Charles is the epicenter of the merged Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe, Indigenous peoples who settled on the island after being forced from other territories by the federal government's Indian Removal Act and related policies. According to the Louisiana Office of Community Development, the island has eroded down from more than 22,000 acres total to just 320 acres due to climate change-induced sea level rise, the oil and gas industry's destruction of the freshwater marsh system, and increased hurricane onslaught.

In 2015, leaders of the Isle de Jean Charles Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Tribe (IJC) determined that due to the ongoing land loss, the tribe needed to relocate. In 2016, the Department of Housing and Urban Development awarded a grant for that purpose, promising that tribal leadership would retain control of the initiative.

However, over time, the government seemingly hijacked the narrative of the resettlement, depicting it as a government-originated plan to help the tribe rather than a self-help effort. Worse, all mentions of the tribe were removed from government website materials about the Isle de Jean Charles relocation. By 2019, the tribe had been shut out of the resettlement decision-making process.

While a resettlement stipulation was that the vacated island would be left to nature, the tribe began to suspect that the agreement would not be enforced. The Houma-based Dupont Corporation tried to sell off land on the island into a subdivision of fishing camps (outdoor vacation destinations). Though the company ultimately dropped the pursuit, the notion was enough to deeply upset the tribe.

Today, most of the IJC Tribe has moved into the resettlement site, but it is still fighting forms of disaster gentrification, including the Terrebonne Parish School Board's 2021 decision to close the Tribe's culture-driven school École Pointe-au-Chien.

What's more, as that Louisiana community has long faced disaster gentrification, so, too, have a myriad of nearby bayou communities in Terrebonne Parish, namely Chauvin and Dulac.

The Terrebonne Situation: Who's Your Neighbor?

Kellie Luke, a librarian for the Terrebonne Public Library System's Chauvin Branch, said that in some cases, the post-Ida cost of home insurance became as high as a mortgage payment. She said such costs make it hard for people who both want to stay in their community and those who want to leave. Would-be buyers can't afford it, and with no feasible buyers, would-be sellers can't sell.

"We've had a lot of people that's had to relocate," said Luke. "[And] the ones that stayed—a lot of them are just struggling now to get their lives back in order. It's hard for anyone to put the pieces back together."

Amberly Champagne, another Chauvin Branch librarian and a resident of the area for the last 22 years, added that storms even upend the lives of people who were financially comfortable beforehand.

"They could [have lived] the rest of their lives with their paid-off home, paid car," said Champagne. "But then you get a storm that comes and destroys your way of living."

Candace Chauvin, manager of the neighboring library branch, noted it can be especially difficult for elderly residents. With limited fixed incomes, if they suddenly must pay even $300 for home or flood insurance, that's a significant chunk of what they would otherwise spend on things like groceries and medicines.

Along with such individual-level impacts, the housing market distortion can also significantly alter interpersonal dynamics woven into the whole community. Thibodeaux said the Chauvin area gradually became a renter-heavy community. Because renters don't have to take on flood insurance costs, there are more renters in the market than buyers. Not only does that mean people who want to sell have to settle for renting out their homes, but also, gone is the local tradition of people owning family properties and building them out with new homes as the family grows.

Still another disaster gentrification-linked tension point lies between community members and outsiders: wealthy individuals or business owners that seemingly swoop in to snatch land. Residents believe these buyers grab properties at post-disaster discounts to either expand their corporate operations (namely gas and oil), create tourist-geared fishing "camps" for recreational fishing and other nature-themed getaways, or even resell for profit in the future. In any case, the wealthy buyers' market presence drives the housing and insurance price hikes which financially displaces residents.

"Eventually…the people with the most money will be [all that's left]," said Chauvin. She noted that while continued price increases may force her and her husband to sell their home, "[Dulac] is always gonna be a hot fishing spot for doctors and lawyers that can afford to have a camp."

The notion begs the question: Could a future where the Chauvin or Dulac are 100 percent camps be possible? If that's too extreme, how else might the communities be forever changed? One answer lies within the infrastructure changes already seen.

Infrastructure in Flux

To date, perhaps the most visible disaster gentrification-linked infrastructural changes lie within the public school system.

Belinda LeBouef, a community member who visited the library one day in May 2023 to work on forms for post-Ida recovery aid, went to Upper Little Caillou Elementary in Chauvin as a child. Now, she's 30 years old and has a daughter in the school and said that the school system is now in utter "devastation."

Upper Little Caillou is one of the five schools in the district—which encompasses all of Terrebonne Parish—that were destroyed by Ida. The district managed to sustain operations for all schools by transitioning classes to modular buildings on-site or at other school sites within the parish. It plans to eventually restore all five ruined schools to permanent structures. However, some of these solutions, whether temporary or permanent, have complicated consequences for residents.

For example, Upper Little Caillou Elementary was relocated to a site in Houma, about 18 miles north of the school's pre-Ida location. Though district public relations officer Leonard Folse noted that the district provided busing to the new site, LeBouef said the geographic change made it harder for her and her husband to drive their daughter to and from school, as the Houma site is significantly further from their workplaces. Folse acknowledges that due to the geography of the bayou communities—only one long, narrow road in and out of the areas—even small changes in mileage can double the travel time.

Regarding that same issue, as part of the Ida rebuild, district leadership opted to permanently move Lacache Middle, which serves students in Cocodrie, one of Terrebonne's southernmost communities, to the site of its companion high school. This means Cocodrie students will have to be transported about another 10 miles up the bayou.

The Lacache move is just the latest in such permanent changes, as the district board made substantial facility decisions even before Ida. This includes its 2021 decision to shutter the Indigenous French culture-based school Pointe-Aux-Chênes Elementary School on claims that enrollment had significantly declined, rendering the school not economically sensible. Rejecting that notion, the Point-au-Chien Tribe argued that then-pending disaster mitigation initiatives, like the Morganza-to-the-Gulf levee project, would minimize the environmental issues they believe have driven displacement. Therefore, enrollment will soon bounce back.

Despite such protestation, the board shuttered the school. And though the community bought the building and reopened the school as École Pointe-au-Chien in 2023, the shuttering still rings as a continuation of a trend that began with the board's closure of several other schools due to low enrollment-based resource consolidation.

Other infrastructure is in flux, too. For example, residents mourned the loss of one of the few remaining grocery stores throughout Terrebonne's bayou communities, Pointe-Aux-Chene Supermarket, which was permanently shuttered after Ida. Similar post-Ida casualties that residents noted include a locally-owned gas station in Dulac; a fast-food place in Chauvin; and a popular bar Harbor Light Marina in Cocodrie, the unincorporated village South of Chauvin.

Jonathan Foret, executive director of the South Louisiana Wetlands Discovery Center, even cited Harbor Light as one of the properties caught up in the kind of post-storm land grab that residents loathe. The bar was once owned by a local couple, but assessment records show the current owner of the Harbor Light and surrounding property is Hilcorp Realty, an offshoot of Hilcorp Energy Co.

That ownership change is unsurprisingly troubling to folks, given that Hilcorp (owned by Jefferey Hildebrand) has an extensive track record of clashing with locals (as covered in a three-part investigative series by The Revelator) and the oil and gas industry as a whole has long been Public Enemy No. 1 to many Louisiana residents.

What's more, as places shutter, besides perhaps oil entities and fishing camps for and by the wealthy, the communities are also not seeing new businesses arise. "There are no grocery stores down here, no banks… nothing," said Chauvin.

Thus, the closure of the supermarket—which had worked hard to stay open through storms and the pandemic—as well as other stores makes the food desert fate a very real possibility for communities. That's a dangerous manifestation of the disaster gentrification that's taken hold.

The Terrebonne Situation: Upsides and Future Forecast

Fire department operations also took a hit from Ida. Most critically, Ida destroyed Dulac's Buquet Bridge, which provides access to the Southernmost part of the Grand Caillou Fire Department's coverage area. Without it, response times to areas below the bridge have doubled, and repairs have not even yet begun.

While the down bridge is therefore a long-term issue, neither fire department leader believes their teams are experiencing issues linked to disaster gentrification. That's primarily because even with some staff leaving temporarily or permanently due to storms, the departments have maintained personnel numbers, and the department leaders don't expect long-term disaster-based municipal budget issues.

But that is just one silver lining amid the otherwise apparent disaster gentrification in Terrebonne Parish's bayou communities of Dulac and Chauvin. The communities' identities are being reshaped by lost businesses, the stripping of the school system, frustrations with excess costs of rebuilding and insuring homes, and annoyance with the outsiders exacerbating that market problem by land grabbing.

These forms of gentrification have long been developing, with Ida only accelerating the situation. To hear residents discuss their current living challenges is to understand that if such gentrification changes continue, those who reside in the bayou communities might one day be shocked by what their hometown has become—just as New Orleans native Adrinnie Duchane now feels about her hometown

Former Chauvin fire chief Marty Thibodeaux, for one, already sees such marked differences.

"[South of Boudreaux Canal], there were once a thousand families that lived down there; now there's only maybe 20 to 25," said Thibodeaux. "A little bit at a time… The face of the community is changing."