This article was produced through the Environmental Justice Oral History Project, a digital hub that combines oral history, student journalism, podcasting, events, and research to document culture and environmental racism in the U.S. South.

On Monday, May 8, 2023, there's varied activity in the small community libraries of Dulac and Chauvin, neighboring bayou towns in Louisiana's Terrebonne Parish. Dulac is the quieter of the two, yet in both locales, there's an atmosphere of warm familiarity, with staff and visitors sharing energetic small talk or chatter about life struggles. In the Chauvin library, visitors use library resources to deal with paperwork for Hurricane Ida government recovery assistance. Much of their chatter is about the storm and the recovery process.

The community members detail how their lives have been—and continue to be—impacted by seemingly endless environment-based strife: The destruction Hurricane Ida wrought in 2021, the exorbitant real estate and insurance price hikes that follow every such climate disaster, the inadequacy of government response to Ida and preceding storms. The list, unfortunately, continues.

However, for all the challenges locals note about life in bayou communities, they have as many reasons for not wanting—and often being unable—to leave, including a sense of community, financial and logistical limitations, and perspective on the risks versus benefits of relocating.

Reverence for a No Stranger "Way of Life"

In the general public consciousness, small, remote, or rural towns are uniquely associated with multigenerational nesting, a concept that has different forms. In one form—which often stems from choice and privilege—this nesting might look like a young couple venturing into a rugged place to "strike out on their own" and then setting down roots for generations to come. In another form, it's Black and Indigenous folks, those previously entrenched in the land by slavery and sharecropping, fight their way to become landowners and attempt to build their generational wealth.

In either form, one of several logistical side effects emerges that perpetuate the generational loyalty to the land. That is, with each new generation, a family tends to get larger, so if one generation wants to move—due to climate issues or any other reason—they must find the financial and transportation means to move potentially dozens of people to keep the family together, or they must be willing to leave relatives behind. For most people, the former option isn't possible, and the second option is too undesirable.

"There's a place I could move to, Lake Arthur," said Kellie Luke, a Chauvin librarian. "It's the most wonderful little sleepy town. But my family's not there. My grandchildren are here."

Additionally, generational continuity and limited population in small, non-urban towns are believed to foster more neighborly closeness than in high-density, transient localities. A 2018 Pew Research study found rural residents are more likely than others to say they "know all or most of their neighbors" and are more trusting of their neighbors. The individuals in the Chauvin library on that Monday in May attest to that.

"Most people down here have never met a stranger," said Luke. "Everybody knows everybody."

Belinda LeBouef, a Chauvin library patron, seconded that, saying her daughter has attended the same schools she once did, with some of the same teachers. Locals relish such connections, and the human ties contribute to a deep-seated reverence for the land—or place—itself.

For example, when some folks, like Kellie Luke, think back on their childhood, they think of the place—the bayou, the campground—where they spent summers and weekends hanging out on the water with their parents, siblings, and kids of other random families.

"It was one big party," said Luke. "We'd stay out [at our camp] two weeks at a time…just out there in the water and lovin' life."

The landscape is a part of their memories, their relationships, and in some cases, their livelihoods.

"This is familiar, this is home," said Amberly Champagne, another Chauvin librarian. "It's a culture. It's a way of life."

No Means for a "Restart"

Even if people are willing to walk away from their homes and the ways of life they know and love, sometimes, they simply can't because they don't have the financial resources.

One element of that resource limitation can be linked to multigenerational nesting. That is, sometimes a home is passed down through generations because each new generation sees the home as a financial asset they can't afford to pass up. When a third, fourth, or later generation accepts a passed-down home, they likely do not have to bear the expense of a mortgage, since their predecessors would have already paid off the property, and the family now owns it outright. So, the newest generation of adults settle for their real estate inheritance, even if it means remaining in a high storm risk community.

"Nobody has that type of 'restart your life' money, or savings account sitting in the bank…to put a downpayment [on a new house]," said Dulac library branch manager Candace Chauvin. "If you own your land and you own your house, you will do anything to keep it."

Indeed, even if a home is damaged by a storm, it is often financially easier for locals to fix what's been destroyed—regardless of whether it happens repeatedly—than to buy a new home somewhere else. For example, the median price of a single-family home in Houston, which many Louisianans move to after disasters, was reportedly $345,500 as of June 2024. Comparatively, according to Gulf Coast Insurance Attorneys, the average cost of storm repairs is about $10,000 for "moderate" wind-based damage, and a minimum of $4,000 to handle water damage. That's less than a quarter of a new home price. Add in price-gouged flood insurance costs and consider a scenario of heavy damage, rebuilding is still a fraction of buying anew.

Younger folks might be able to afford a new home if they were to get a job in a new community, but there's no guarantee. They might face a weak job market or prejudice, as some bayou natives might be perceived as less qualified for the types of jobs that exist in non-coastal communities.

Some locals admit there's some justification for this assumption. After all, besides the oil and gas industry, Terrebonne Parish's economy comes predominantly from shrimping (or other fishing), and, as Father Antonio Farrugia, pastor of the Dulac Church Holy Family, and Dulac resident Craig Luke both explained, bayou shrimpers and fishers tend to not have a formal education. This might make it difficult for them to secure other jobs.

What's more, unemployment is not the only risk people face in choosing to move.

For Better, or Worse?

People could have the resources and desire to move—and do so to be safe from physical harm during a storm or the mold of post-storm-soaked ceilings and floors. But moving could supplant those health risks with others.

For example, Elizabeth Boquet, a Terrebonne Parish native who now lives in Connecticut, said the mere process of moving can take a toll on people's health, due to the disruption it brings in day-to-day life as well as physical exhaustion from travel, anxiety of getting used to new surroundings, and physiological responses to a new geographic environment. Boquet believes her own mother's fate proves the health risk of moving.

She said that after shuffling her parents back and forth between Connecticut and Louisiana due to a string of disasters—Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Hurricane Gustav, and the BP oil spill in 2010—she and her husband moved her parents to Connecticut for good. While this proved beneficial for Boquet's father and long-ailing mother in some ways, Bouquet believes there was a major pitfall.

"I am 100% certain the move and the [associated] discontinuity of care…accelerated [my mother's] death," said Boquet.

Also, when multiple generations are forced to merge into one household, elder family members can become more vulnerable to disease than when they previously lived alone, because they're living with younger relatives who, through work or school, have a high risk of illness exposure. There was evidence of such intergenerational infection with COVID-19.

Along with the uncertainty of how health might be impacted by relocation, Dulac and Chauvin residents wonder if relocating even brings reduced risk of experiencing environmental disasters.

Humans Can Run, but Not Hide

Kellie Luke summarized common local sentiment about whether anywhere is "safer" than their home communities: "There are [climate] disasters no matter where you go."

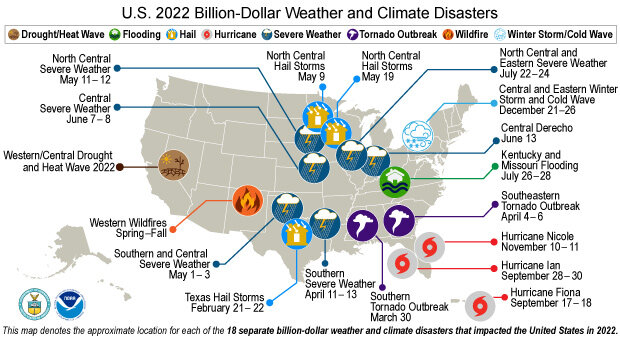

Indeed, Louisiana doesn't even rank in the top 10 of the U.S. News & World Report 2021 ranking of the most disaster-prone states—Texas and California top the list. Also, several places have experienced geographically uncharacteristic environmental disasters or at least events. For example, the East Coast recently had a generally harmless but resident-shocking earthquake incident. In June, a flurry of tornadoes hit Maryland in greater number and severity than has ever been typical for the region, and scientists are ominously predicting the second coming of the disastrous 1930s Dust Bowl.

And, every US region faces threats of some combination of extreme weather events, including tornadoes, hurricanes, wildfires, winter storms, earthquakes, tsunamis, landslides, and volcanic eruptions.

"You can go to Tornado Alley and ask everybody, 'Why do you stay?'" said Amberly Champagne. "This is the area we're in! [Are we] gonna migrate for [all] storm seasons? No!"

Champagne's point is founded. However, statistically, some places do fare worse than others regarding disaster susceptibility. For example, the U.S. News & World Report list shows a clear spectrum of quantities of disasters per state. Also, Louisiana has sustained the third-highest damage costs total of all states (based on data from 1980-2022), including Hurricane Katrina, the costliest climate disaster in the US to date.

Additionally, among experts in the climate change space, it's commonly accepted that sea level rise is inevitable and will be increasingly significant through 2050. Mathew Sanders, a senior officer with The Pew Charitable Trusts who previously spent almost a decade in Louisiana state and local policy work, said some places are sufficiently safe from sea-level rise in the long term because they're well-elevated. At the same time, Sanders said some places have already degraded so much they can't be salvaged, and the trajectory of further degradation can't be stopped or reversed quickly enough by any mitigation efforts, like raising or fortifying homes, or building infrastructure to curb flooding. Sanders said relocation is not just the alternative to mitigation, but the only viable option.

"The way that our risks are expanding on an incremental basis far exceeds our national ability to invest in mitigation activities," said Sanders. "Even if we had all the money in the world."

Sanders said some people, especially residents in vulnerable communities, resist this notion. Dulac resident Craig Luke (no relation to Kellie) is relatively accepting, noting that "mankind has always migrated," for environmental and other reasons

Indeed, scientists and archeologists have found evidence that there's always been some dynamic between human migration and the environment. The changing climate revealed land bridges that made migration possible. Climate change from the earth's axis movements is believed to have created massive shifts in vegetation, which would have impacted food supply and thereby influenced movement.

But at the same time, as such historical evidence supports Sanders' notion that relocation is inevitable, it also supports the notion of human adaptation. That is, humans learned to live in new climates when they moved for various reasons in the past. So, why can't humans learn to live with the climate circumstances of today, instead of fleeing from sea level rise and volatility? That's essentially what people in disaster-prone communities, such as Louisiana's bayou towns, have always done. It's been something that many low-income and/or BIPOC groups have been forced to do, as centuries of systemic oppression practices such as land-grab displacement, geographic segregation, and red-lining have put certain communities in vulnerable positions even before climate crisis threats emerged.

"Just Deal With It"

For bayou natives, storms have been so intrinsic to their upbringings that they are not horror stories, but amusing anecdotes. For example, Kellie Luke said families and neighbors even throw parties in acknowledgment of pending hurricanes. With her own birthday in September—the middle of hurricane season—she spent childhood birthdays playing in hurricane waters.

Sometimes, families get together more so by necessity than to simply make the most of an uncontrollable situation. But even in cases where the storm is more severe, there's a comfort in coming together with their loved ones to weather the storm—whether it's multiple families convening in whoever's coastal home is on the highest ground, or families taking road trips to out-of-state relatives' places.

"Storms are a part of life down here," said Father Farrugia. "You just deal with it."

Also contributing to the lack of doomsday mentality is the fact that locals have seen unpredictability in storms, furthering the notion that they can't always be evaded.

For example, on August 26, 2005, Hurricane Katrina was on a trajectory to directly hit the Florida panhandle. Yet, over half a day, the modeled path shifted west—with the eye directly in the center of the Gulf, which would have meant Terrebonne Parish faring worse than New Orleans in terms of Louisiana danger zones. Then, the hurricane quickly shifted toward New Orleans. Thus, New Orleans was devastated, but Terrebonne was relatively spared.

Conversely, in 2008 with Hurricane Gustav, Terrebonne Parish sustained more damage than New Orleans but did not suffer as much as expected—especially compared to the Caribbean and Cuba. Then, just a couple weeks later, Hurricane Ike hit, and Terrebonne significantly flooded. With Hurricane Laura in 2020, the bayou communities were virtually untouched, but Lake Charles, which lies about 200 miles West of Dulac and further off the Gulf, took a beating.

"You don't know which hurricanes are gonna hit, and where they're gonna hit, and who's gonna be devastated," said Candace Chauvin.

This makes people hesitant both to evacuate for storms and to leave for good even after a storm wreaks havoc. They feel it might be a waste of money and energy. But people aren't just staying put and sitting idle.

"People are more open to finding a solution so they can stay because they don't have the money to leave," said Chauvin.

Innovation for Preservation

Terrebonne Parish locals have raised their homes on stilts—from a few feet to as tall as 12—to avoid flooding. They've also used metal materials to fortify their roofs against hurricane winds.

Craig Luke said his roof only lost a few shingles in one storm, but the gap allowed water to get in, which wrought water and mold damage. Afterward, he fortified his shingles by screwing metal brackets everywhere he had rafters and ceiling joints.

"I can tell you right now, my roof system in my house is not gonna pull apart," said Luke. "It's impossible 'cause it's screwed in place."

Then there are community efforts. The most significant is the Morganza-to-the-Gulf, a levee system spanning about 98 miles across Terrebonne and Lafourche parishes. After more than a decade of research and development, Terrebonne leaders presented a formal project proposal in 2006, arguing that the expansive levee and lock system was critical to the future of both parishes.

The project was federally authorized in 2000, but as Luke summarized, in recognition of the impracticality of waiting for federal funding, the parishes introduced a local sales tax to finance the project. Six years and $18 million raised in state and local dollars later, construction was initiated. In December 2012, Terrebonne residents voted for another sales tax to complete the Morganza system's first levees and floodgates. Construction is ongoing, but federal funding to advance the project has since been approved. Forty-five miles of levees and floodgates are under development as of June 2024.

Dulac residents are thus far pleased with the results."We've had tremendous success," said Luke. "Without those levies… we could possibly be uninhabitable right now."

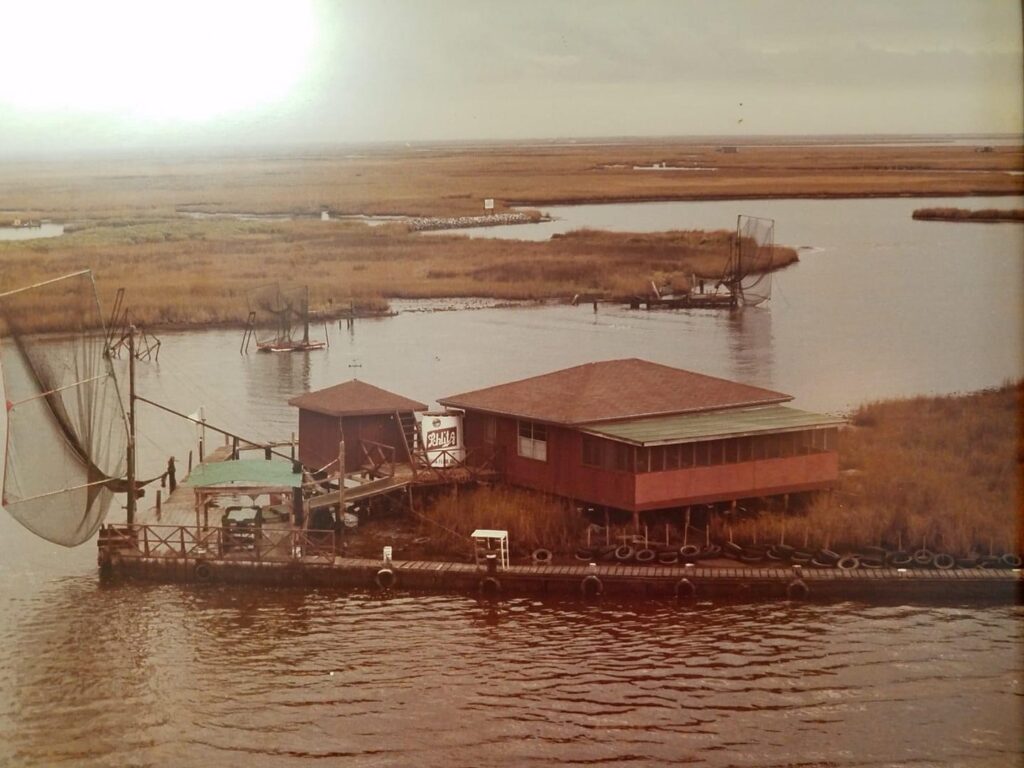

Kristina Peterson, a facilitator for Louisiana bayou preservation-focused nonprofit, Lowlander Center, noted several other bayou resident-led endeavors. She said one family in nearby Jefferson Parish attached wheels to all the kitchen and office equipment in their home and restaurant business so they could easily evacuate the items and save them from upcoming storms. Similarly, after it was destroyed in a storm, Boutte, a restaurant in Lafitte, was rebuilt on a barge to better withstand future climate disasters.

Peterson also said tribal communities of the bayou areas, such as in Grand Caillou and Pointe-au-Chien, are addressing flooding-based shoreline erasure that was infamously caused by oil and gas companies digging canals by filling in canals and building living shorelines. Meanwhile, the First Peoples Conservation Council is also reshaping and fortifying shorelines by developing oyster reefs; Lafourche Parish is allowing the conversion of individual and community spaces—including businesses and government entities—into floating docks to adapt for when flooding makes areas accessible only by boat; and Grand Caillou has introduced the Netherlands-based concept of floating gardens.

"People aren't standing by hopelessly," said Peterson. "They are thinking in innovative ways."

There is a sense throughout Louisiana's bayou communities that government entities could be better supporting their efforts. For example, the government seemingly hasn't explored backfilling canals, according to Jessica Simms, program officer of the National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine's Gulf Research Program. This particularly frustrates locals because they believe the government bears responsibility for allowing the oil and gas industry-based canals to be built—and as such, is to blame for the resulting exacerbation of climate threats.

Folks condemn other government decisions, too, such as installing levees in the Mississippi River at the expense of the natural flow of sediment and thereby the shoreline, and they criticize the latest approaches that government entities are taking to "solve" climate threats.

Simms suggests there's a heavy focus on managed retreat, such as the recently implemented, controversial decision to move the Indigenous people of Isle de Jean Charles off the ever-shrinking island to a new settlement on higher ground. Then there's the federally funded Morganza to the Gulf project, which expands the levee system in Louisiana and can be classified as a mitigation measure, or a way to ensure that when hurricanes do hit, the damage isn't as bad. While this approach arguably lessens the need for relocation, it can also be seen as prioritizing protecting structures, rather than addressing the systemic oppressive actions and policies that have caused the threats from which structures are being protected.

At the same time, the state of Louisiana's primary plan for dealing with climate threats is the Coastal Master Plan. The plan is heavily comprised of measures to restore the coastline, but some critics argue that with the perceived lack of attention on stopping coastal erosion, restoring the coastline is yet another bandaid and not a long-term true solution.

Peterson believes that the government would be more effective if, in a broad sense of disaster and climate crisis planning, it incorporated the concept of Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or Indigenous techniques centered on ecosystem dynamics.

She added that because the bayou communities "are still a viable place that seafood gets harvested for the rest of the country, oil and gas gets produced for the rest of the country, ports still bring things in and out," government efforts to be more effective in long-term climate management wouldn't just benefit the bayou communities, but the entire coast [and subsequently, the country].

Yet whether the government improves its support efforts or not, it's clear locals are determined to stay in their homes, come whatever climate threats. And their reasons vary from necessity to practicality to sentimentality and everything in between.

"It breaks [peoples'] hearts to leave everything they're familiar with," said Chauvin resident Amberly Champagne. "[Even if] it was for the better… it would make me sad if I had no other choice but to go. This is just—it's home."