Climate change and the frequent extreme weather events it causes have ushered in an epoch marked by successive disasters that plague Southern communities at a disproportionately higher rate than their regional counterparts. Scalawag has long centered environmental racism and the Southern tradition of resisting it in our publishing and this year was no exception.

As 2024 set and broke more records for extreme events, the South weathered successive major hurricanes, a long summer heat wave, and massive floods in the face of state abandonment and capitalist exploitation. And as we have always done, mutual aid networks and community support proved to be our best bet against extreme events. From firsthand accounts of navigating climate extremes in prisons to rural communities' long recovery from major storms and our first eco-poetry series, here are the 2024 stories that defined "climate resilience" in Southern terms.

In this piece, incarcerated journalist Kwaneta Harris provides a firsthand account of the horrors she and her fellow inmates endured while attempting to survive Texas' summertime extreme heat events in the state's non-air conditioned prisons.

"Living under this heat dome triggers asthma attacks, back-to-back seizures, and chest pains. Showers are held hostage by people refusing to exit the only cold working shower shared between 43 people. In this foxhole, enemies become friends and friends become family. There's no room for dignity, pride, or bias. We share a common deadly enemy: the extreme heat."

Gentrification is often considered an urban-suburban phenomenon, but as climate change makes all communities more vulnerable to the devastation of extreme weather, Amanda Ostuni's coverage of Louisiana's Terrebonne parish's recovery from Hurricane Ida brings rural gentrification and displacement to the forefront, destabilizing this notion.

"For any disaster-stricken community, their plight does not end when storm winds die, floodwaters recede, and fires are extinguished. Rather, a bevy of subsequent problems emerge, and a community may never be the same again. One such problem: swiftly after disaster events, insurance price hikes and land poaching commonly unfold in storm-swept areas."

In Louisiana's rural Terrebonne Parish, Amanda Ostuni uncovers the harsh realities legacy community members confront when deciding whether or not to leave their homes following disastrous weather events. Home equity, close communal ties, and poverty are among the many barriers small-town Southerners face to leaving, despite the devastation.

"However, for all the challenges locals note about life in bayou communities, they have as many reasons for not wanting—and often being unable—to leave, including a sense of community, financial and logistical limitations, and perspective on the risks versus benefits of relocating."

In this coverage of disaster recovery in Louisiana's rural Terrebonne Parish, Amanda Ostuni focuses on the many hurdles communities face in accessing recovery assistance and coordinating with state priorities to fix damaged infrastructure, especially when those communities are small, rural, and predominately Black.

"High-powered winds were the driving force of the storm's impact, but much of the recovery struggle community members have faced stems from problematic elements of the aftermath—including the time it takes to repair and restore infrastructure and the complexities of the procedure for obtaining recovery assistance."

Mississippi native novelist and climate activist Mary Hegler draws powerful connections between the winter floods in Gaza and the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927, trans-historically suturing the two events by their shared cause: settler colonial violence.

"Like the flood in Jabalia, the story of the Great Mississippi Flood starts with settlers. When the first settlers arrived in the region, the Indigenous people warned them to expect the river to flood every 14 years. Instead of accepting their wisdom as a fact of nature, the settlers took it as a dare and set out to put the mighty river in her place. They, of course, thought of the river through a colonial lens: man vs. nature. Settlers and planters (as plantation owners, who rarely touched dirt, were known) built a hodgepodge levee system in an attempt to wall the mighty river off."

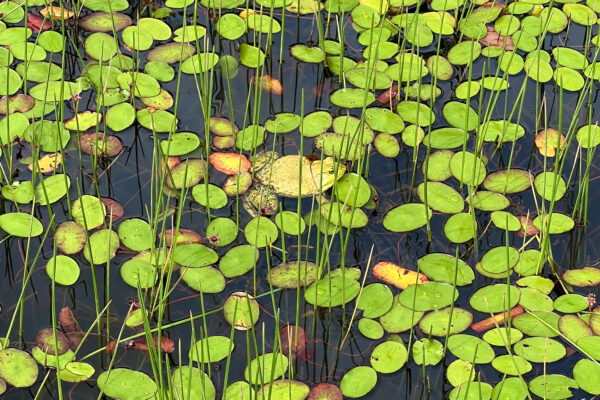

Hurricane Season series editor, Aarohi Sheth, marked the beginning of this year's storm season by curating Scalawag's first eco-poetry collection. In it, they platform a few of Houston Texas' best local poets' musings on climate change and its impacts on their beloved hometown.

"The South's land has a particular kind of poetry to it—one that's always catching its breath among oil rigs, histories, connectedness, heat, pollen, kinship, sacredness, wetlands, and flash floods. And ecopoetry has long been a space to reimagine a climate future in which we survive. It's a way to a world inside us—and beyond us. It urges us to sit with words until they become shades of growth, bloom, and decay. But ecopoetry doesn't just encompass the wonder of nature and "finding" oneself, but labor and dailiness."