As a Black, queer man born and raised in South Florida, the history I've been taught in schools and formal settings has followed the same pattern: emphasis on "Black history" remained relegated to the white supremacist textbook narratives of the period from enslavement to our eventual emancipation. If I was lucky enough to have a Black teacher, they would slip in some additional tidbits regarding our Black history, introducing us to new facts about our culture we, as Black students, had not been knowledgeable about otherwise. Regardless of Black educators' best efforts to intervene, Black History stuck to the Florida state-approved tradition of largely alienating Black students from our culture. Now, thanks to Governor Ron DeSantis and his continued efforts to stop the teaching of critical race theory through censoring African American history in Florida's schools through bills like the Stop W.O.K.E Act, the "tradition" has made the history curriculum even more regressive. Fortunately, I have learned more about my Black history, especially as it relates to South Florida, from the Black people in my community who have both lived it and are dedicated to its preservation.

This family history, preserved through spoken stories, photos, and more, allowed me to learn the most about the place around me that I call home.

My family members who grew up in Dade County have had the most significant impact on learning South Florida's rich Black history. My mom's first-hand experience in particular, which included stories of her attending Dade County high schools during desegregation—which took place way after segregation was deemed illegal—and many others that chronicled her life as a young Black girl living in Opa Locka is among my most cherished lessons. This family history, preserved through spoken stories, photos, and more, allowed me to learn the most about the place around me that I call home. Today, against the constant attacks on even the most minute bits of South Florida history, two notable Black cultural workers, Nadege Green, creator of Black Miami Dade, and Emmanuel George, creator of Black Broward, help to preserve our vibrant local history.

Black Broward

Emmanuel George, born in Overtown, Miami and raised in Broward County, is the lead archivist and creator of Black Broward. Growing up in South Florida, he, like myself, learned about the Black history of Broward County through those around him and his research. George cites Dr. Kitty Oliver as his "mother in historical spirit" and her book, Race and Change in Hollywood, Florida, as one of the main catalysts that jump-started his journey into meaningfully engaging Broward County's Black history. From discussing the shared history and connection between the cities of Danie and Liberia in his 2016 documentary film, A Tale of Sibling Communities; Danie and Liberia, to highlighting and featuring various Black historical facts about the county on the Black Broward Instagram page and in the Broward County digital archive, his work helps to showcase the often unseen and unknown history that exists in the county. And it has not come without pushback.

Due to both Florida's current political climate and its long tradition of censorship and sanitization in relation to race and Black history, creating and maintaining a resource like Black Broward comes with several hurdles for the archivist. While George acknowledges those who came before him, like Kitty Oliver and Ernestine Ray, he is one of the few dedicated to doing this work in the digital age. "A lot of challenges I dealt with head-on. Lack of funding, having to pick up other jobs just to sustain in what I'm doing, it was hard," said George.

Nevertheless, since creating the Black Broward platform in 2016, George has expanded its offerings far beyond its initial concept. Ahead of the election, resources like Black Broward's archive proved to be vital pieces of the past that helped inform our voting decisions. According to George, his research serves "as an index and aid for helping certain people [politicians] and certain things when it comes to politics." Recently, he has also used Black Broward to guide Fort Lauderdale's exhibition on the desegregation of schools in Broward County, further exemplifying the importance of his work and its impact on people living in the county.

"By getting younger people into preserving and documenting history, it can create future archivists, storytellers, and preservationists of tomorrow."

Emmanuel George

As someone who has called Broward County their home for most of their life, I can honestly say that many of the tiny tidbits about the county I have learned have come from the Black Broward platform. Following the Instagram page since 2022 has allowed me to learn so much about Black life in the county, including some relating to my hometown of Miramar and other neighboring cities like Hallandale and Hollywood. More than just an educational resource for Broward County residents like myself, Black Broward is a considerable historic preservation effort for Black people in the South Florida region and beyond.

"The work can still be seen and appreciated by making the work intergenerational," said George. One way George is bringing this to fruition is by working in collaboration with Broward County high school students to conduct interviews with alums from three historically Black high schools: Blanche Ely High School, Dillard High School, and Attucks High School.

MORE IN HISTORIC PRESERVATION:

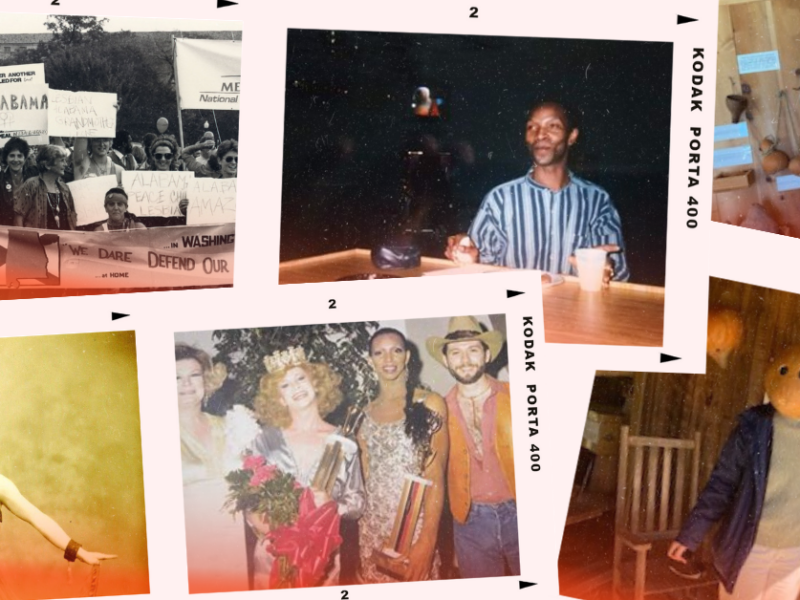

The first Black drag queen in North Alabama and other untold stories of the Queer South

An exclusive look into the Invisible Histories Project collection: From lesbians with gourds on their heads in rural Georgia to a 1980s Birmingham bar called Mabel's Beauty Shop & Chain Saw Repair.

By connecting with the community to further his work efforts, George is part of a new generation of archivists. "By getting younger people into preserving and documenting history, it can create future archivists, storytellers, and preservationists of tomorrow." George added that these young archivists can use preservation to uncover and uplift different perspectives within the Black experience in Broward that have yet to be substantially covered, like Black LGBTQ+, veteran, and more social life stories. With the growth of the Black Broward platform and the burgeoning new voices to tell these stories, the history of the Black Broward County experience continues to grow.

Black Miami Dade

Born and raised in the county of Dade, writer and researcher Nadege Green is the creator of the platform Black Miami Dade. The resource, serving as a piece of archival Black Miami Dade County history, comes from similar roots as archivist Emmanuel George's Black Broward project. "I was pretty fortunate because I grew up in Miami's Black communities, and I've always been around elders who were generous in sharing their stories. So while the teachings [regarding black South Floridian history] didn't necessarily come from school proper, they came from the community," said Green.

"Anchoring ourselves in stories of resistance and fortitude of those who came before us and demanded that democracy works for them is something we absolutely need, especially going into this election year."

Nadege Green

While the attacks and threats from Desantis do not affect the work put into independent platforms like Black Miami Dade, Green acknowledges it does have an overwhelming effect on how school curricula handle Black history as a whole.

"It does affect the work of folks who are in our public school system who could literally lose their teaching license. Some teachers are debating what kinds of history they should discuss, whether they should even discuss specific topics, or whether they should self-censor to preserve their positions. It's detrimental to our education system as a whole, and that's why there must be community spaces where this history is available." More often than not, community hubs like libraries, churches, and more now bear the responsibility of preserving and passing on Black history that can be taught outside the primary school system.

Black Miami Dade, one of these essential resources, has flourished within the Miami-Dade County community. From community members finding people they knew on the page to Green receiving her flowers for the history the resource brings to light about the area, Black Miami Dade only continues to grow in both presence and impact.

One example of its impact that I'm grateful for Nadege Green mentioning was her "Give Them Their Flowers" exhibit. Curated with Martha Vickles, director of education at the Peréz Art Museum, the exhibit ran from March 13 to April 23, 2023, and was the first of its kind in Miami. The exhibit showcased the often untold history of Black, queer life that exists in the city. The show was an important intervention, as depictions of Miami's black history often exclude queerness while those of its gay history often exclude Blackness.

READ MORE:

The Candy Shop: Columbia SC Rallies to Honor Landmark Black Gay Bar

Commemoration is also meant to speak to a young generation of LGBTQIA+ South Carolinians, letting them know that today's struggles have long histories, their queer elders are standing with them, and they belong.

"When I did that research, it came out as an exhibit, and it came out in a Black neighborhood by design, and I look back at how that exhibit was received within Black Miami…it was tears, it was hugs, it was like a family reunion," said Green.

This exhibit not only provided a space for the community and other visitors to learn about Miami's Black queer history but also allowed for the communal sharing of oral histories. This especially resonated with me as I never learned much about South Florida's Black, queer history while coming into my identity down South. Knowing that exhibits like this exist can help community members in Miami learn more about those around them. They also allow Black LGBTQ+ community members in the city to see themselves represented in history right along with everyone else. This preservation of physical artifacts, practices, and stories helps keep these stories and this history alive in the community.

Another piece of preserved history that Green discussed is Langston Hughes's poem on Miami, "The Ballad of Sam Solomon." The poem tells the story of Sam Solomon, a Miami resident and activist who encouraged Black voter turnout in the 1930s in the historically segregated city of Overtown. To help inform more of the community about the poem and create an open space for conversation, Black Miami Dade, alongside the Maven Leadership Collective, helped organize a poetry speakeasy in the heart of Overtown with this poem serving as the centerpiece. Participants were even able to take a copy of the poem home. "Anchoring ourselves in stories of resistance and fortitude of those who came before us and demanded that democracy works for them is something we absolutely need, especially going into this election year," Green said. The preservation of these historical and cultural artifacts informs us of our past and allows us to continue to press forward for new changes for our future."

So why does preserving our history matter? It helps us acknowledge a past we have yet to adequately understand and discover as we continue to savor and preserve our present so that future generations have something worth looking back on. The Black history of South Florida is something that even current and prior residents don't fully know about. The efforts of Emmanuel George at Black Broward and Nadage Green at Black Miami Dade give community members a space to remember, mourn, laugh, and share comfort. As someone who will represent Broward County and South Florida until I turn blue in the face, I believe that resources like this are necessary for me and others to meaningfully connect with the past. South Florida's Black history deserves to be preserved.