Brother,

We used to know the feeling well—family—maybe more than we knew each other. You came of age when I was young, too young to know love further than Super Mario and SweeTarts and too long ago for me to remember now. I came of age when you were gone, first for a few years with the army, then to the South's mecca for carefree Blackness. We are both of age now, and it's funny. I still do not remember you, save a couple of fleeting years before the trauma. And, you are still gone, now to the unrelenting mystery of mental illness. Schizophrenia. In that erasure and absence, I have become resigned to finding family in unimpressive places, forcing it when it is not meant to be, and imagining it when all else fails, when all else falls. I rediscovered a book recently, Houston Baker Jr.'s I don't hate the South. It made me think of you, of us, of family.

"Life swings just like the trapeze, and our arms live in naked hope. Family bodies hurtling toward us at high speed in midair don't allow choice."

Love requires that we catch them, those family bodies, blood or not, heavy and clawing, sometimes pulling away even at the risk of peril. Love says that we fight for them, with few qualifications, because sometimes they require the infantry, and even by the stingiest of definitions, love makes us soldiers, blood or not. And, sometimes we need their love, more than the light, more than the truth, more than the hope that we are forced to conjure after they've gone, so we stop their fall and hold them close, head on shoulder, eyes shut, sometimes forgetting who it is, exactly, we have caught. In I don't hate South, Houston warns, "The first failure is reason. The first and only virtue is love. If you do not catch the ones you love, you die—now or later," and if they are in free fall, however long since they let go or jumped or surrendered, not catching means they die too. I think.

Brother,

I found it the first time on Jesse's syllabus, a jewel in a succession of books on Blackness, Black expressive culture, Black identity, Black Studies, and fried chicken. I took as many notes as I could on it, with pens and pencils and sticky notes and an old highlighter that I had taken from grandma's house that I used on every word of Langston's "The South":

the lazy, laughing South

With blood on its mouth

The sunny-faced South

Beast-strong

Idiot-brained

The child-minded South.

The New South. The rising and risen again South. The "past is never dead, it's not even past" South. It was all familiar, unlike anything that I had read before, yet all so very familiar.

I found it the next five or six times in all kinds of places, once after I had finally lost the fear of seeing myself in my work and again after buckling under the heaviness of what that meant. I found it this time in the fifth box, at momma's house, pages slightly worn, margins filled with notes-to-self and words that I didn't know yet. "Prolix." In total, I have read I don't hate the South maybe eight times, more than any of the other 182 books that I own. I have sat with it—which is to say, sat with jarring reflections of my own southern life—at all hours of the day and night, meditating, like Houston, over the ugliness that sometimes muddies the beauty of it all. I did not expect that this night and that unimpressive place, among unpacked moving boxes in the dimly lit guest room of mom's house, would feel like family, and I did not know that this reading of Houston was a reading of us, that in his gripping story of family and mental illness, you were his son Mark and, for you, California was in the South, the wilds of Los Angeles County somewhere beneath the Mason.

I don't hate the South tells a lifetime of stories, many from Houston's life, some from the ink of famous pens, some the lore of his father, and some the voices of the land, the South. The stories reconstruct Houston's coming of age—Black and southern and the son of a father who was faithful to his stubbornness unto death. The book begins with a fall, as Houston is struck by his father for dancing and singing with too much looseness and falsetto suitable for any boy or man, especially any boy or man carrying the distinction of his father's name. The fall sent Houston up from the basement and out into the winter cold of his hometown Louisville—but not before his father's warning, "Damn it! Houston Jr., stop acting like a sissy." Stop acting like a sissy, and mind the family lineage, which passed through heroic Black women and light-skinned Black men, pimps and housemaids, preacher uncles and church mothers, and all the book learning that growing up Black before 1930 was supposed to deny. Stop acting like a sissy, and be a gentleman, which by his father's standards, meant being a, "financially secure, literarily and musically cultured, Christian, superbly coordinated athlete who knew how to navigate a sixteen-piece dinner setting" and who, above all else, was a man, which was something altogether different.

Encyclopedias and other reading material were as common as coat racks in the geography of Houston's childhood, and among the newspapers—stacked in kitchens like plastic-bag-filled plastic bags—and magazines—on coffee tables like lamps with bad bulbs—he found a love for reading, an enchantment with learning. He agitated his brother by practicing pronunciation on family road trips, he collected 10-cent payoffs from his father each time he finished a book, and he often found himself on fantastic escapades in the Louisville Public Library. From the library, we learn of Houston's affinity for one book in particular, The Souls of Black Folk, for him the lynchpin text in the literary canon of the American South, a roadmap to the infinite gifts of Blackness. Houston calls it a "southern book written by a New England black genius."

Brother,

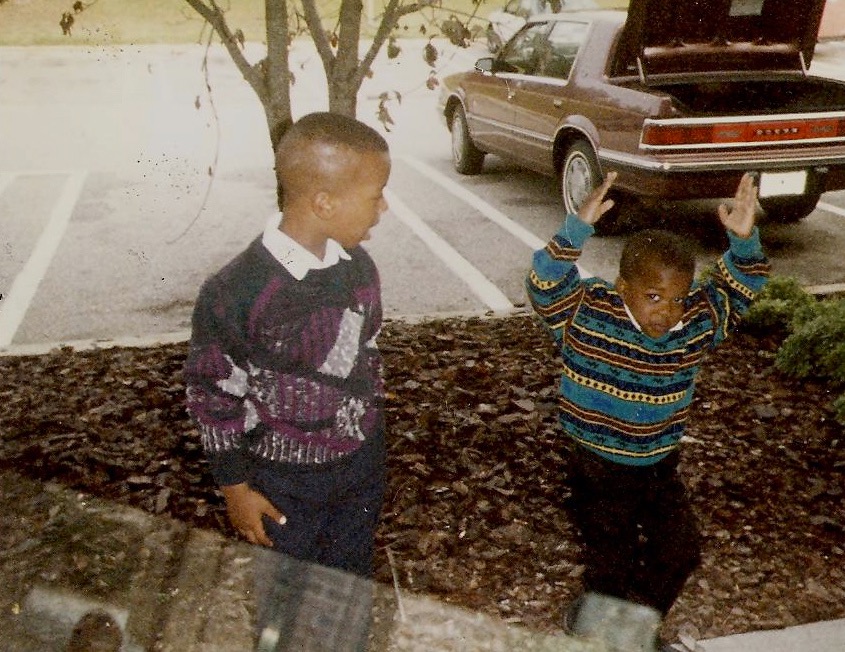

I was 21 when I first read Houston, and his chapter on Souls was the first time I had seen "black" and "genius" placed so closely together, in text and uninterrupted, but for a time in my early teenage years, I watched you serve the type of Black genius that was the stuff of legend, at least in my world. Your two little brothers wanted to be just like you, ole fast-talking, big-word-using, weight-lifting, smooth-dancing, Tommy Hilfiger-wearing, dope-ass-CD-collection-having, city-living ass nigga. So, we practiced. I read as many books and magazines as I could get my hands on. Blake started lifting weights. I danced. We labored over our Tommy Hilfiger outfits, matching colors and patterns and soaking them with ironing starch. We listened to what you listened to. TLC. Janet. Prince. Whitney. We visited, as often and for as long as Mom and Dad would allow. Some of the best times of my life, until they weren't.

The tipping point came sometime around 2002. Mom and Dad had agreed to let us stay for the entire week. We made it to day three. We were walking to the park, a July Fourth celebration I think, when it turned—loud yelling, sharp curse words, and, eventually, marching orders. We were to take the metro back to your apartment, two Mississippi kids, neither of us older than 16, fighting through the city looking for home. I still don't know what brought about that episode. Maybe you saw in us the vast darkness of homophobia and abuses that you had grown familiar with back in the country, that you had thought would disappear under the city lights. Maybe we brought back memories of violence, our spirits like fists from fathers who were dead and dying, even though we didn't know it yet. Maybe it was all normal; you were just having a bad day. Either way, we never really got past that.

Houston wrote his dissertation in eight months, in Scotland, with his wife Charlotte, and under the blessings and financial backing of his father. At 25, he found himself on an advisory committee for Black Studies at Yale. It was 1968. By 1970, three things had happened. First, Black Studies had arrived at Yale on the shoulders and backs and lips and in the laps of the Black Panthers. Houston describes that time as "revolutionary," complete with tear-gas canisters and about 15,000 people who had the audacity to imagine a post-imperialist America. But, winter—and revolution—comes strange in New England, especially for Black folks from places like Kentucky. That year, Houston and Charlotte moved to Virginia, happy for the greenness and warmth of Spring. That was the second thing.

Sometimes, though, the South gets cold too, leaving us vulnerable, wanting of home, momma's cooking, and grandma's hands. Wholeness. Wholeness, like sweet potato pie fresh from the oven, or at room temperature on day two, or settled from the coolness of Saturday night. Wholeness, like fishing with grandpa, sitting on emptied five-gallon buckets, lightning bugs dotting the distance, us more afraid of unhooking our unlucky harvest than of the boogey man. Wholeness, like when the music cuts, and we are surrounded by people we love, blood or not, and we all know the words, and we rap them as if they belong to us. Houston refers to this deep desire for wholeness as the "poetry of impulse," the grand narrative of Black southern consciousness—which is to say, American consciousness—embodied in the stories of Cane and Bigger Thomas, the lives of Zora and Ida, the words of that Black woman living in Louis Armstrong's trombone.

"To my father's mind, the only true sign of family for the black fathers was the salvation of their sons."

The third thing that happened in 1970 was the birth of Houston and Charlotte's son Mark. By Houston's account, Mark moved quickly from seven pound-eight ounce bundle of perfect stillness, to carefree Black boy laughing and singing and dancing, to "happily and safely positioned" Ivy-League-graduate-turned-Ph.D.-aspirant, to one of the smartest kids in his class, until he wasn't:

Mark's first violent, delusional, psychotic crash in the uncontrollable throes of bipolar disorder hit our family in the summer of 1996. In retrospect, we know the horrific, obscene, name-calling, physical-violence-threatening argument at the end of our journey to Los Angeles was symptomatic…. His thoughts raced him into delusional provinces of extraterrestrial voices, sightings—messianic visions that exhorted him to rescue "the black nation" from slavery, to marshal an army under the flag of Uranus and march among unenlightened whites to victory!

Crashes often bring the end, of a misstep, of an oversight, of a life. For Mark, however, the crash was just the beginning.

When Mark reached us by telephone, he was not "Mark Frederick Baker," but someone bearing that name—a disembodied voice strangled by unreliable beliefs, narratives that carried traces of the sulfurous hell of delusion. He was convinced he was under surveillance by creatures only he could see. He snatched a $50 bill from his companion's pocketbook and fled their Los Angeles apartment. "Mark, where are you? Do you know where you are calling from?" My wife pleaded into the telephone shaking in her hands.… It turned out he was at a restaurant-and-bar pay phone, in the wilds of Los Angeles County: desert territories never meant for a metropolis.

Houston and his wife had to go to Los Angeles. They had to catch their son, or who was left of their son, to help him out of whatever undone situation he had wondered himself into. Houston imagined the advice his father might offer in advance of this trip. "First, I know the only thing that will be present when you get there is what you have sent ahead. I also know you always have to take care of your 'base,' which means being good at the art of catching" (173). Like so many other nodes in Houston's life—reading, pedigree, New England—"the catch" was an inheritance, in his mind an act of love, sometimes mundane and unfantastic. It was his father presenting his would-be arresting officer with proof that they had paid for admission to the stadium. It was his wife's iron grip on the phone, whispering sweet nothings and stank prayers long after her sweet nothings and stank prayers no longer had an audience. Catching is sending new letters to old addresses, filling up answering machines, wiring money, calling numbers that lead to operators. Catching is finding wholeness where it ain't none at, imagining it when all else falls.

Brother,

We stumbled at first—an argument here and there, a month or two without communicating. I was angry with you about a lot, about that third day in the city, about the way you talked to mom, about you failing my expectations. That anger made not remembering come easy, and when I moved away for school, you became nothing more than a remnant, like an old toy or video game on Christmas. I know forgiveness is supposed to help with that, but my stubbornness, no doubt made in the image of dad, made forgiveness strange to me. All them Sundays and Wednesdays and Saturdays spent in church, all them big words and all them books, but I had not yet learned forgiveness, which, I think, is born from love, which comes before the catch.

The fall was spectacular.

The autopsy report would have read "Assault (homicide) by blunt object," or whatever they write when someone dies under the shadow of a bat and fists in the southern night. You were close, as close as when I saw "black" and "genius" pushed together in Houston's book, as close as daddy and I were the day before he died. The details of your discovery are missing from the stitched-together story that I know, just that someone "came along and found you" folded over yourself in a dumpster, one dirty shoe to your name.

Perhaps it was the work of a burned lover, his hands hoping to spill from your body the recompense for some dark deed, or secret, or trespass. Perhaps it came from the shadows of the streets, black magic in the magic city. A mugger. An addict. A dealer. Perhaps you said the wrong something to the wrong someone, and it drove them to try and kill you. It could have been any of these, or none at all, but for at least a little while down in some dirty pocket of south Florida they found you dying. John Doe.

You would have been John forever, if not for mommas—mommas and their sweet nothings, stank prayers, and iron-fisted grips that hold silent phones, whipping switches, fly swatters, stirring wheels, pie crusts, bleeding sons, medication, and all the love in the whole wide world. The catch.

Momma cried. She told them she couldn't come, that her husband was dying—he only had a few days left, we just didn't know it yet—anything to delay the truth that she already knew. Two days later, she was on a bus from North Mississippi to South Florida. It was Thursday. Y'all were in Memphis by Saturday. The story—of getting there, getting you, and getting back—is hers, but I hope she will share it with you one day, and I hope you carry it always, even in those times when you forget what family feels like, or lose yourself in the painful memories that were.

If time seemed real back then, we could have made one of those schedules that middle class families affix to their refrigerators and bulletin boards to keep up with their weekly obligations. We were planning Dad's funeral. Grandma was in the hospital, undone by the sight of her only son lying in wake at 5:22 a.m. in that cold hospital bed. You were in the psychiatric ward. We stretched as far as we could, ambitious hopes of catching everyone.

You spent the next two months at Mom's house. The assault had taken so much from you, replacing all that I had known and tried to forget with a constellation of violent delusions and hallucinations. You told stories of advising state senators and presidents, being surveilled by secret societies, and rocketing through orbit. In the intermediary moments, when your body had the strength of movement and the meds had started to wane, you turned—loud yelling, sharpe curse words, and, eventually, marching orders. You were not nearly recovered from the trauma, you wouldn't take your meds without Mom's insistence, and you were sick, but none of that mattered. You wanted to be gone. I think I did too. According to my journal—I have no recollection of this—I took you to the bus station a week after grandma's funeral. Gone again.

The years have passed by slowly—seven and counting since I've seen you, five since we last talked. I wonder how you've been, if you've caught up with who you used to be before, if there can be any permanence with who is left of you now, if you still find yourself wondering into dark places like presidential boardrooms, old sheds in the green of the woods, or out through the black, cold heavens. I wonder if I can read enough books to learn "forgiveness," if I can find it without first finding the love that sat in our togetherness with dope ass music in the background.

"The aerialists ascended long, chrome ladders to small perches aloft. They set the bar in motion, gripped and committed, swinging into open air toward the catch. The Flying Wallendas did it with ease—the daring young men on the flying trapeze! Would that man suspended only by the crook and grip of his knees on the other side always make the catch? I remember his naked arms—muscled flesh alone. His face an impassive smile, until the instant of meeting the fingers, hands, and wrists of the body tumbling into his catch. An unheard connection, as certain and holy as saving grace."

I get it. I think. Family bodies—whether blood or not, heavy and clawing, or pulling away—fall, and we catch them, partly out of the mundane duty that love enlists, partly because that love, wherever it is directed, is required if we are to become whole. What is less clear to me, I guess, is what to do when that catch comes from another place, from the memory of a love that used to be but no longer is. Do we still stand with them clinched tightly between palm and forever, or do we sometimes, even after all the labor and love and sweet potato pie, have to let them go? And, who is to say that we, because of our presumed sanity or good fortune, favor or privilege, are not also falling and in need of being caught.