Early morning, April 2017. I drive from my Kansas City home to Texas, to meet with 33-year-old Marleny Menchu Gaspa, a Guatemalan woman held at the T. Don Hutto Residential Center outside of Austin.

The center holds mostly Central American and Mexican women caught entering the United States illegally. It is named after Terrell Don Hutto, a cofounder of Corrections Corporation of America, now called CoreCIVIC, which operates several private prisons and detention centers, including Hutto. Before it contracted with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2006, Hutto had been a medium-security state prison.

Grassroots Leadership, an Austin nonprofit that advocates on behalf of Hutto detainees, arranged my visit. Before I left Kansas City, I spoke by phone with Mimi Lawrence, a Grassroots volunteer. She described Hutto to me as a place with high walls, guards, metal doors, scanners.

"Airport security stuff, the whole bit," Mimi said.

Mimi began seeing Hutto detainees in 2014—her "amigas," as Grassroots volunteers refer to the women. Before each visit, she checks the ICE website. If she doesn't find a detainee's name, they're gone. She can only guess what happened. Asylum, transferred, bonded out, or deported.

Mimi recalls one detainee, a Honduran woman who wanted to be a teacher, interrupted her studies to flee gang violence. Very sweet person, 20-something. On one visit, Mimi mentioned that her husband had been hospitalized for knee surgery.

"I'll pray for you," the woman said.

She gave Mimi a prayer book and a friendship bracelet. Mimi can still picture herself sitting on a bench outside her husband's hospital room, the prayer book in hand.

"What happened to her?" I asked Mimi.

"She didn't make it," Mimi says. "She got deported."

The Center stands just outside Taylor, Texas, population 14,000, about an hour north of Austin. The wire fence surrounding the white, block buildings suggests a housing project. More than 500 women live behind Hutto's walls. I walk inside and a guard asks me to sign in, remove my shoes and the contents of my pockets. I step through a body scanner, just as Mimi described.

The guards are friendly. They comment on a storm that recently drenched Taylor and all of Austin. But I still feel their distrust. Their work requires a level of suspicion that casual conversation can't conceal.

A guard escorts me into a large, brown carpeted room. Heavy blue chairs occupy the center. Dim lighting scarcely illuminates the pale walls. Three plexiglass cubicles, designed for legal consultations, take up one side. Near one cubicle, a boy and a girl, the children of a visitor, play with Legos. I sit in one of the chairs and wait for 33-year-old Marleny, the woman I have come to see. The facility's policy prohibits me from bringing in a pad and pen for notes. After we speak, I will hurry out to my car and jot down what I remember.

Marleny walks through a door. She wears blue sweatpants and a T-shirt. She sits across from me, hands clasped on her lap.

"Can you adopt me? Can you help me?"

She smiles. Joking. Acknowledging the impossibility of her request.

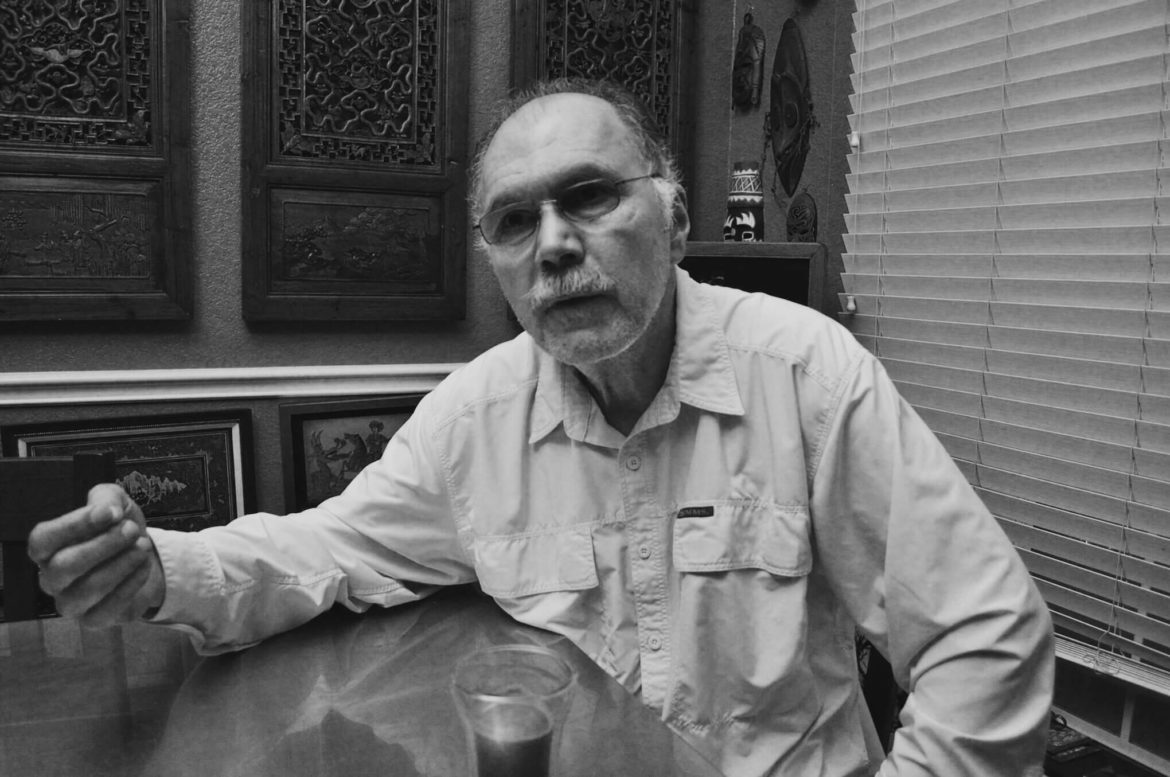

The next day, on another rain-soaked morning, clinical psychologist John Rubel greets me at the door of his suburban home, not far from Taylor. Rubel worked at Hutto, but left because of what he considered to be the administration's interference with his work. After making himself a double espresso, he joins me at a table. When we begin talking about the facility and the women detained there, he answers my questions with a slow deliberation. Sometimes he says, "Golly," when reaching for an answer.

Rubel worked at Hutto from 2013 to 2015. He never imagined himself at a detention center. Originally, his plan had been to graduate with a marketing degree and work in his father's water well business in upstate New York. One day, a professor suggested he enroll in a personality theory course, to help him understand the individual impulses that influence markets. Rubel followed his advice and found he enjoyed the writings of Freud so much that he switched his major to psychology.

After completing a graduate degree at Chicago's Forest Institute of Professional Psychology in the mid-1980s, he accepted an internship with the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

We have a slot, an administrator told him. We'll send you to a federal prison in El Reno, Oklahoma.

"Where's that?" Rubel asked.

"Go south," he was told.

After 26-and-a-half years, Rubel retired from the Federal Bureau of Prisons and set up a part-time, private practice. Three years later, in 2013, a colleague told him that Hutto had an opening for a clinical psychologist. Rubel considered it. There was one drawback: he didn't speak Spanish.

"I'll return to Guatemala," Marleny said. "Don't take my daughter."

"Too late," the officer told her. "You're with us now."

"You might want a bilingual psychologist," he told Hutto administrators.

They disagreed. Most of the healthcare staff didn't speak Spanish, either. Rubel could hire an interpreter. He accepted the job, clueless, he admits, about immigration issues and the detention system.

It surprised Rubel to learn that private prison companies house more than half of the detainees in the United States. Detainees have no constitutional right to a lawyer, because they are not citizens and are not facing criminal trial. Many do not speak English, have no criminal record, and have committed no wrongdoing other than entering the United States without a visa. That in itself is a civil violation, not a criminal offense.

Like immigration detainees in other centers across the country, the women at Hutto are held like prisoners while not being considered prisoners. In his years working for the Federal Bureau of Prisons, Rubel had never experienced anything like this. Most of the detainees were in their late teens or early twenties. Rubel felt he had entered a high school, except all the young women were locked up.

"Like a prison," he says.

During my visit at Hutto, Marleny tells me that she grew up on a coastal farm in Guatemala with six brothers. She and her brothers helped their father harvest tomatoes and corn. When they weren't working, they played marbles and flew kites.

A 2007 flood ruined their land. Neighbors became ill from drinking dirty water. They developed rashes. Marleny's family could no longer grow crops. She was 23, young and eager, and desired a better life. She told her father she wanted to live in the United States.

"We will live simply and get by," her father insisted.

Eventually, he conceded that the farm had no future. It made sense for her to leave. Marleny traveled north by foot and by bus through Mexico. She crossed deserts. She saw mirages of cities. Near the Texas-Mexico border, she noticed that mesquite trees had been trimmed to reduce cover. Twice, border patrol agents caught her and sent her back to Mexico. She crossed successfully on her third attempt and made her way to Houston. From there, she took a bus to Los Angeles, where an aunt lived.

Her aunt had legal status. She wanted Marleny to work in a neighborhood bar that needed a waitress. Marleny refused; she didn't like bars and the people who frequented them. Her aunt insisted. It would be a job. Marleny still said no. Her aunt put her out of the house for the day to break her resistance.

At a nearby park, Marleny found herself sitting beside a woman who knew of a Hindu restaurant that needed people, but it was too far to walk. To earn money for bus fare, Marleny made tostadas and sold them door-to-door. In this way, she met a Guatemalan man living in the same building as her aunt. He worked as a fruit vendor. He was not a U.S. citizen. After a while, Marleny moved in with him. They had two children, a boy and a girl.

Marleny and the children's father lived together until 2011, but their relationship was unravelling. Marleny's father was sick with cancer, so she returned to Guatemala by bus to care for him. She took the children with her.

Seven months later, her father died. Marleny stayed on to help her mother. She began a relationship with a man who became physically abusive. She worked and saved money to leave him and return to the States.

In August 2016, Marleny bought a ticket to fly her children to their father in LA. She would cross into the U.S. by herself. But her daughter refused to leave without her. Her son flew to California alone.

In October, Marleny and her daughter took a bus to Hidalgo, Texas, a port of entry. She told U.S. Customs and Border Protection officers that she was fleeing her abuser and requested asylum. An officer told her she would be placed in detention. Her daughter, an American citizen, would be removed from her care.

"I'll return to Guatemala," Marleny said. "Don't take my daughter."

"Too late," the officer told her. "You're with us now."

Marleny held her daughter for what felt like hours. Then an officer gripped her from behind while another pulled her daughter from her arms.

"Momma, help me," the girl cried, Marleny recalls. "Tell them I want to be with you."

Marleny says she collapsed in tears. She was bussed to Laredo Detention Center, where she applied for asylum. In November, she was transferred to Hutto. Authorities released the girl to Marleny's aunt in LA, who turned the girl over to her father. As the biological parent, the father is entitled to custody and guardianship of his children, regardless of his status. Unless ICE detains him, he can remain in the United States with his children.

Marleny tried to hold her family together with phone calls, but her daughter's father told her to stop calling.

"Our daughter gets upset when she talks to you," he said. "She wets the bed." The father recently put a block on her calls.

"What if I don't get asylum?" Marleny asks me during my visit. "What if I'm deported? I'll never see my children."

She cries. A guard brings her Kleenex. I watch her wipe her eyes but I can think of nothing to say. Finally, I thank her for her time. I wish her good luck. Before I leave, I see a guard scan her with a wand, presumably to check if I slipped her something. Then Marleny stops at a door, opens it, and I no longer see her.

At his kitchen table, Rubel tells me that every woman he counselled at Hutto had experienced something awful prior to their detention. Sexual assault was common. As part of their initiation into gangs, young men allowed gang members to rape their girlfriends. Gangs also extorted families.

Other detainees experienced the horrors of the road. A coyote kidnapped one detainee and raped her repeatedly for seven days. A teenage detainee saw a friend cut in half after he fell off a freight train in southern Mexico.

"If you were a butterfly, which one would you be?"

"Why that one?"

"It's free."

"I like the color."

"It's big."

"It's beautiful."

None of the women came to Hutto directly. They were first detained in temporary cells in south Texas ICE stations that the women called "hieleras," or ice boxes, because of their frigid temperatures. Immigrant rights groups accuse U.S. Customs and Border Protection of deliberately keeping the temperature low to pressure detainees to agree to deportation.

If a woman decided to fight her removal, she might spend 10 to 12 hours on a bus bound for a detention center without any idea of her destination. Single women without children landed in Hutto. They stayed about six to eight weeks before an immigration judge decided their case.

At Hutto, prison jargon interspersed with normal speech. Detained women made up the "population." They had "uncontrolled movement" within the "facility." At certain times of day, they stood for a "headcount." They had "access" to a gym, art and English as a Second Language (ESL) classes, and other various indoor and outdoor "activities." At night, they slept in two-person, 9-by-12 cells. No bars, but the doors could be "secured."

Stress took its toll. Hundreds of confined women who didn't know one another had to get along. They confronted a legal system they didn't understand. They worried about their families back home. They agonized about being deported. Their health suffered. Twenty-year-old women complained of chest pains, loss of appetite, headaches, and nightmares.

After his first two weeks counseling at Hutto, Rubel concluded that he could not hold individual therapy sessions for so many detainees. He developed group therapy programs instead. Participation was voluntary.

"Come once a week while you're here," Rubel told the women. "I can help you manage your emotions, show you how to handle your fears and all the stress you're under."

He facilitated three groups a day, five days a week. Eight to ten women attended each group. They sat in a circle, introduced themselves, and said where they came from. Honduras, El Salvador, Mexico, Guatemala. In one exercise, Rubel asked yes and no questions. Whoever answered yes stepped into the circle. Almost all of the women stepped in for every question.

"Who has children?"

"How many of you have parents who are still alive?"

"How many of you worry about your children back home?"

"You have a lot in common," Rubel told them. "You're not alone."

In another exercise, Rubel showed the women an ink drawing of a caged butterfly.

"Is this you?" he asked. "Do you sit in a cage all day?"

A few women nodded yes.

He offered a second drawing. It showed dozens of multicolored butterflies fluttering around outside the same cage.

"Get out of your cells," Rubel said. "Take care of yourself."

He distributed pictures of butterflies. Yellow, brown, black, red, green, and many other varieties.

Abolition Week: Stage 1

This article highlights the similarities between detention facilities and prisons and the unique ways in which the realities of detention and prison are exacerbated for women.

While reading this article, consider the following questions?

What is significant about Southern states using former prisons to house detained immigrants? What is significant about the choice of the word "residential" as opposed to "correctional" or "detention?" What is highlighted and what is obscured?

Next Steps: Read Zaina Alsous' interview with Professor Felicia Arriaga and filmmaker Brett Story about crimmigration (the criminalization of immigration), detention, and the continually expanding reach of prisons.

"If you were a butterfly, which one would you be?" Rubel asked.

The women picked.

"Why that one?"

"It's free."

"I like the color."

"It's big."

"It's beautiful."

Rubel gave each woman a picture of the butterfly they had chosen.

"I think butterflies are strong," Rubel told them. "They are also fragile and delicate. They can also travel long distances and survive. I think people are a lot like butterflies."

Some of the women got tearful. They had come to the U.S. with hardly anything. What little they had, border patrol agents took away. Now they had this, a flimsy piece of paper, a picture of a butterfly.

Rubel never knew how long a woman would participate in group. One day they attended, the next day, they vanished. He received no notice about where they might be or why. The absent woman aroused fears of deportation among the remaining women.

"Maria is gone," Rubel said. "Let's stand."

He held a carving of two hands in prayer.

"For those of you who want to offer a prayer, touch the hands. Turn your thoughts over to the God you believe in."

At least twice a month, a detainee received bad news, usually a death in the family. "How do you deal with a sudden loss while locked up?" Rubel asked himself. "How do you say what you need to say to a dying person from your cell in Hutto?"

One woman lost a son to a gang. Shot, murdered. Rubel says it was gut-wrenching to see her. She stayed in the Hutto medical clinic isolation room for a few days just to be alone and grieve.

Some of the guards showed little patience for her tears.

"Go to your room," they said. "You can't be in the common area. You're upsetting people."

Sometimes in group, Rubel asked the women to consider their options should they be deported. Did they fear for their safety? What would they need to do to stay alive?

"How do you want to die?" he asked. He was deliberately provocative, to get the women to release their anger. "Would you fight back? How do you want to be remembered? As a fighter?"

One group participant, Violeta, a Salvadoran woman in her 20s, told Rubel she had no family or friends left in El Salvador. Her father owned a small convenience store. Violeta and her older brother worked for him. A local gang demanded money, and when the family couldn't pay, the gang murdered Violeta's father and brother. Violeta and her mother found their bodies one afternoon when they returned home from shopping. A gang member watching their house shot Violeta's mother. Violeta escaped through a back door.

Violeta told Rubel she believed the gang would hunt her down and kill her if she returned home. She said she'd kill herself if she was deported.

"I'd rather die in Hutto," she told Ruble.

He placed her on suicide watch.

A typical suicide watch rarely lasted more than three days. Violeta stayed in a cell by herself for almost seven. She wore a smock she could not use to hang herself. She ate food without utensils.

Rubel met with her and together they considered alternatives to suicide. She believed suicide was a sin. What would be the consequences if she killed herself? Rubel asked. She did not want to go to hell, she told him.

"Where could you live other than your village?" Rubel asked.

Violeta said she had a friend in another part of El Salvador. The killers would not know she was there.

Options. That was what Rubel wanted her to find. Options to giving up.

After one week of therapy, Rubel removed Violeta from suicide watch. She met with him several more times before an immigration judge denied her asylum claim.

"Send me a note," Rubel told her. "Let me know how you are."

He wrote his Hutto office address on the back of her picture of a butterfly. He never heard from her. He hadn't expected to, not really. Why would she want to remember detention?

Rubel considers his time at Hutto the most clinically challenging and emotionally taxing work of his career. It drained him.

Despite the challenges, or perhaps because of them, it was also his most satisfying professional experience. The groups succeeded. Suicide watches declined as did outpatient psychiatric and other medical care. The women got more active and involved in other center activities: basketball, volleyball, art and ESL classes.

However, administrators at Hutto didn't see the success, Rubel says. They didn't ask, "How can we support you?" Instead, they questioned his methods. "Why are you doing this? Why are we spending so much on interpretation services?"

"They didn't say 'You can't do groups anymore,'" Rubel says. "They said, 'Change the schedule. It takes too much time.' The net result, groups went down to four and five a week. I had to generate a waiting list."

Rubel resigned in 2015, about two years after he started.

"The mission of the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement Health Service Corps is to provide care equal or equivalent to the community standard of care," Rubel says. "It doesn't say, 'We treat only crisis and prevent suicide.' The mission is mental health treatment. It doesn't say, 'We can help you but you have to wait several weeks for a group.' I think that's immoral."

Rubel offers to drive me through Taylor to Hutto. Although I've already seen it, I agree to go to the Center again, to stare at its walls and reflect on my conversations with Marleny, Mimi, and Rubel.

We get in Rubel's car and drive past housing developments and shopping centers, part of Austin's expanding suburban sprawl, until we reach Taylor. Empty 19th-Century storefronts take up much of its downtown. Luxury Inn & Suites advertise nightly rates. Flashing lights illuminate Zapatas Restaurant. Near it are a Quick Way Grocery and ACE Dental of Taylor.

When we reach Hutto, we circle the parking lot and Rubel notes that barbed wire no longer lines the top of the former prison's walls. Rubel pauses by the granite sign, T. Don Hutto Residential Center, and I lean out the window to snap a photo.

The dictionary defines "residential" as "designed for people to live in/providing accommodations in addition to other services/occupied by private houses." Hutto's use of the word accomplishes two contradictory goals: accuracy and deception. Residential sounds better than prison. Hutto's past use, however, leaves no doubt of its purpose today.

From my position outside, I imagine Marleny behind the walls.

I wish I had met with Rubel before I met Marleny. I might have brought her a picture of a butterfly. Or let her choose one from a series of pictures, as Rubel had done. I'll never know which butterfly she would have chosen or why, or if Rubel's analogy worked for her. Still: beautiful, strong, fragile. She is a prisoner but not a prisoner, held in a prison no longer called a prison.

"There has to be a better way to treat these women," Rubel says. "Are they a threat? I didn't think so."

On April 19, 2017 Marleny lost her asylum hearing before an immigration court. She filed an appeal two days later. According to her attorney, and despite the appeal, a Hutto deportation officer is pressuring her to sign her deportation order. She has refused.

A spokesman for T. Don Hutto Residential Center and U.S. Customs and Border Protection refused to comment for this story.