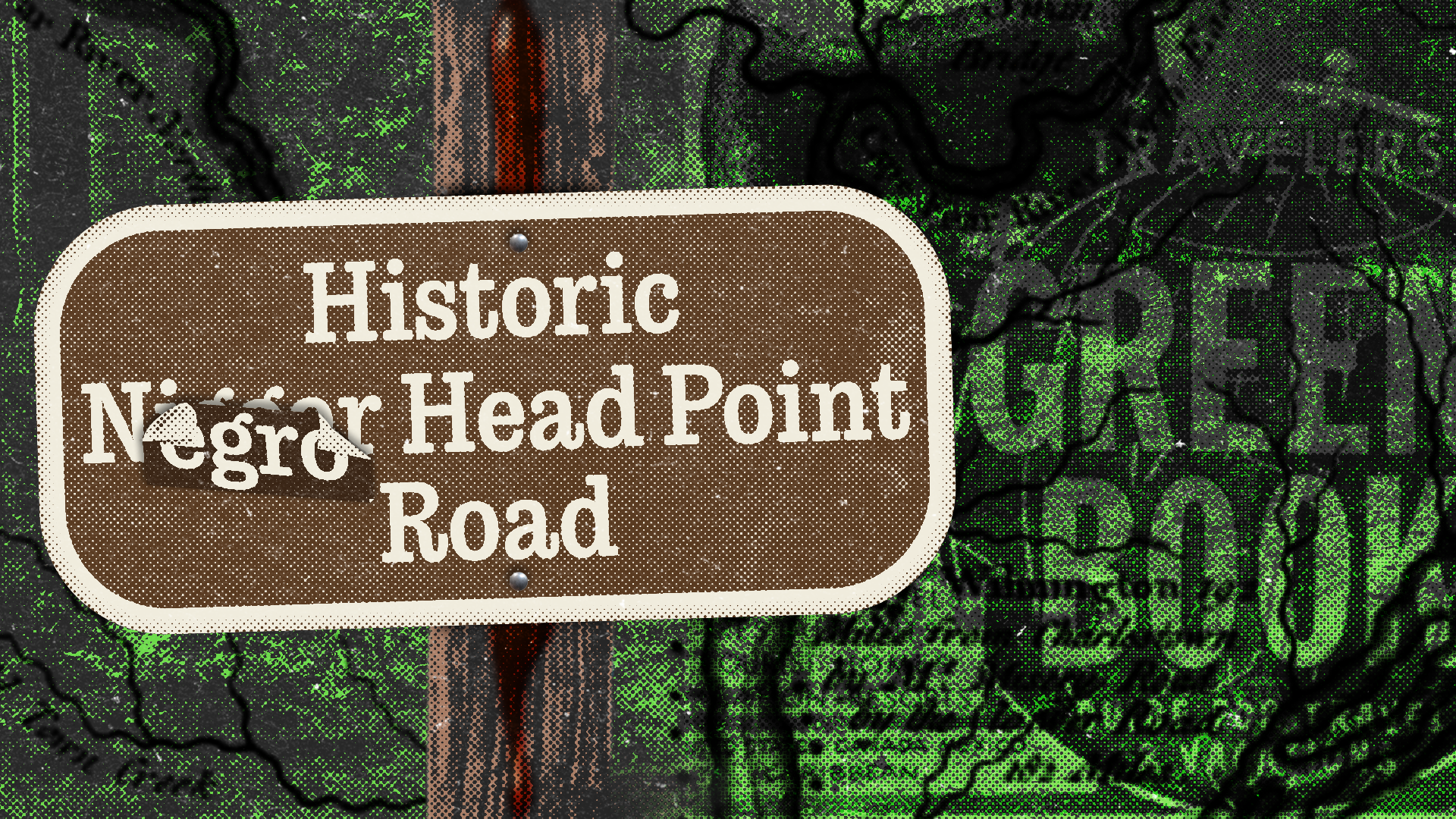

"It was called Nigger Head Road at first, and then they changed it on the maps," my father said. "Right up there, where Uncle Herman's house is… You remember where I took y'all walking that day?"

I nod, thinking back to our early beginnings in Roseboro, North Carolina. We were so little—toddlers—with my oldest brother being the only one in elementary school. I do not remember why our father was taking all five of us—my two sisters, my two brothers, and me—into the woods that day. Maybe Mama needed a break from us. Maybe we just begged Daddy to take us with him, and he gave in. I will never know for sure why we were off to the woods. What I do remember is that our father walked in front of us with his rifle, the one his father had given him, and we followed behind, confident that Daddy would take care of us.

We trailed like ants behind him, excited to be on an adventure with Daddy. I'm sure he stopped often to answer our questions, break up our spats, and make sure we weren't touching anything that could harm us. He didn't seem to have any real destination in mind. We just walked, exploring, seeing, and listening as we were engulfed deeper and deeper into a trail that Daddy seemed to know by heart.

For years, my siblings and I would recount this story to each other. "Do you remember when Daddy took us for that walk in the woods?" It always made us smile, and we would question each other as to why Dad thought it was a good idea to take five small kids into the woods. All we knew was that Mom was not with us and, because Daddy worked so much—sometimes five or six days a week while pastoring a church on Sundays—it made the walk with him even more precious.

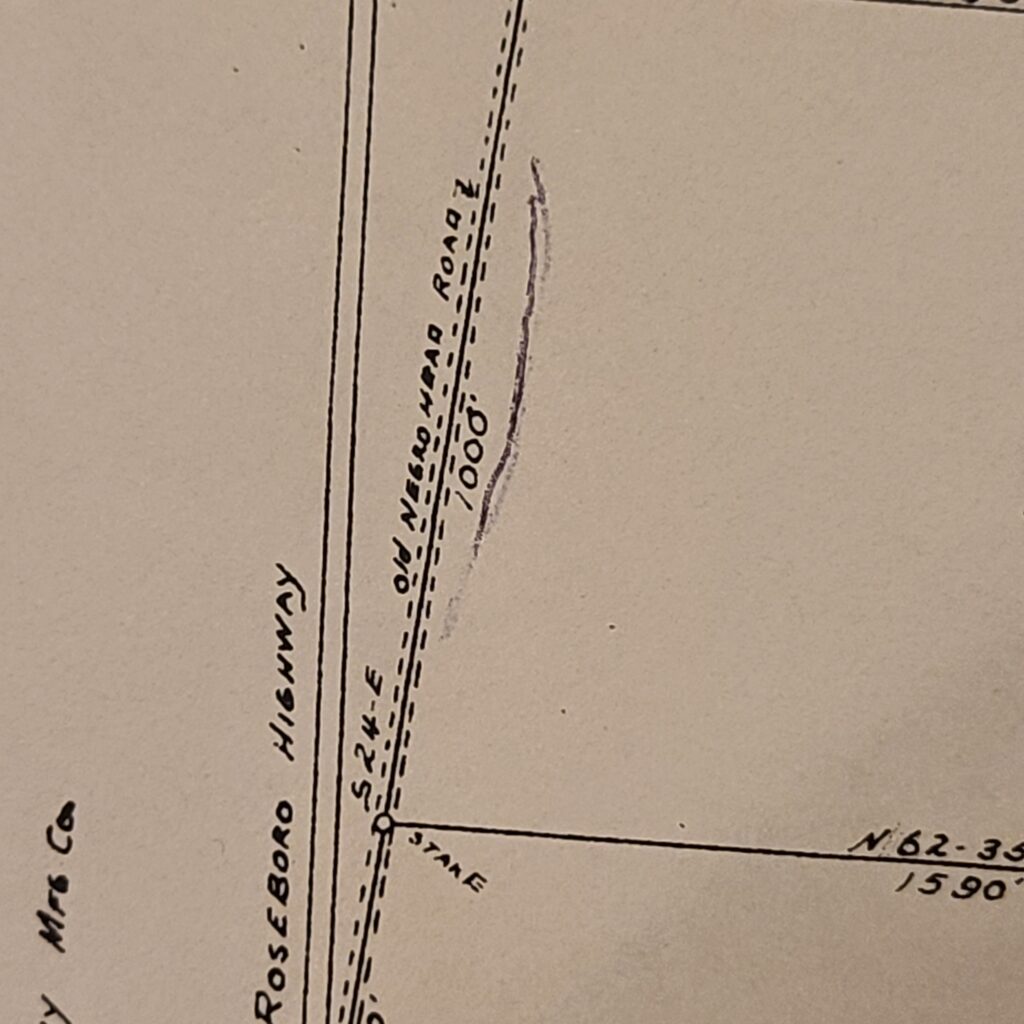

The walk remained a nostalgic memory until the day Daddy began describing the naming history of that very road to me. We were pouring over a map of my grandfather's property lines and he pointed out the road. "Um huh, that's it right there." Scribbled in black ink was a line denoting a road. A name had been written next to it: "Negro Head Road."

I studied the map while Daddy kept talking. "But it was called Nigger Head Road, not Negro Head Road." He spoke with the confidence I have grown accustomed to hearing when my elders describe events and experiences that did not show up in history books or newspapers. It was the same way my grandmother would describe the place "uptown where they hung people" and the field she ran through to "get away from those white men."

It was this matter-of-factness that did not rely on someone else's research. Rather, their confidence stemmed from personal truth and experience because they knew they could not rely on media or archives to share or reflect their stories. The history books, newspapers, and media they had been exposed to narrated the story of America's experiences, not that of the Black experience, especially the Black, rural, Southern experience. So, things had to be stated with a matter-of-factness.

Matter-of-factness is the deeply rooted confidence in which a person erased or made invisible in history speaks their truths. It is also undergirded with a strong desire to make sure the listener understands that the words spoken are indeed true.

In 2017, I had the chance to be a part of a team collecting data on the Washington D.C. Women's March, which was held the day after the inauguration of the 45th President of the United States. The turnout was beyond anything we imagined. I remember striking up a conversation with a Black man who was selling a variety of paraphernalia. Women's March t-shirts, earrings, and bags. Obama posters, visors, and souvenir cups. Even MAGA hats and lapel pins. He had it all. He told me in that same matter-of-fact voice that my father and grandmothers often used, "There wasn't anybody out here yesterday for Trump's inauguration. You could have thrown a rock and not hit a soul." This street vendor knew what my dad and grandparents did. He didn't need the nightly news to report on the size of the crowd at Trump's first inauguration. The media could not un-convince him of what he saw with his own eyes. He had experienced it and that was sufficient enough data.

It was the same way my grandmother would describe the place "uptown where they hung people" and the field she ran through to "get away from those white men."

So, my research into "Nigger Head Road," was not because I didn't believe my father. It was because I knew if I was going to write this article, my readers might not believe my father's words the same way I did. The facts I have gathered are not for me or for him. It's for the people who need evidence to believe what they cannot see or do not understand.

I did not question my father about the naming of the road because, first, we lived in North Carolina, the rural South. The usage of a racial slur to name a road or a person was not surprising. Second, I had heard stories of the times "back then when white people could do whatever they wanted, whenever they wanted, and nobody could do anything about it" all my life. "Negro Head Road" or "Nigger Head Road" as part of the white imagination was not surprising.

What was surprising was when I unexpectedly came across "Nigger Head Road" in a county yearbook dated 1945-1946 in the East Carolina University digital library collection. I was scrolling through each page of the yearbook, thinking I might stumble across one of my ancestors' names when I came to a page entitled "A Sampson Tour." On this page, the author recalled a story that had been retold to her many times:

"Back in 1831 the Nat Turner insurrection broke out in Southampton County, Virginia. It seems that Turner urged the slaves to run away from their masters and when he got enough leaders together, he would start a rebellion. His method of agitating the slaves spread, and soon there were small revolts among the Negroes of Bladen, Carteret, Jones and Onslow counties. When the people of Sampson County discovered an insurrection plot similar to that of Turner, steps were taken immediately to put it down. So they killed the colored leaders and hung their heads on poles along the road as a lesson to other rebellious Negroes. The folks in that section of the county have called the place 'Nigger Head Road' ever since."

My father was right. His matter-of-factness was indeed all facts. What my father didn't know, however, was the reason this stretch of road had been given its unsavory name. The Sampson County yearbook provided the answer. The worn path in the woods that my siblings, my father, and I had tread in the early 80s was the remnants of a road that, at one time, was lined with wooden poles supporting the decapitated heads of alleged slave insurrectionists. These "rebellious Negroes," as the author refers to them, took a chance at freedom over a life of bondage.

But that wasn't the end of the story. It was just the beginning. In a quest to find information about my ancestors, I read A Journey to Sampson County: Plantations and Slaves in NC, which tells a similar story of another "Negro Head Road" in the same county, coined after enslaved men were murdered, beheaded, and staked on poles to warn bystanders against provoking a slave insurrection. I wondered, Could it be possible that several slave rebellions were happening throughout the county? Were there other Negro Head Roads in other states and provinces?

In Southampton, Virginia where the Nat Turner Rebellion occurred, you will find "Blackhead Signpost Road." The road got its name after the 1831 rebellion when the head of one of the slaves who had allegedly participated in the insurrection was put on a stake and left to decompose to deter other enslaved men and women from rebelling. In 2021, "Blackhead Signpost Road" was changed to Signpost Road.

Before you arrive in Wilmington, North Carolina between the counties of Pender and New Hanover, you will find "Negro Head Point" on a historical marker. However, "Nigger Head Point" had been its name in 1760. It remained until the 1960s.

After Nat Turner's Rebellion in 1831, eight men, both free and enslaved, were tried in Duplin County and New Hanover County for leading a slave insurrection. The men were found guilty, killed, and beheaded. Their heads were placed on stakes at different points along the colonial road to advertise that slave insurrections would not be tolerated. Until around 1940, federal highway US 117 was referred to as "Negro Head Road."

There is also Negro Head Corner, Arkansas, but the name is derived from a wooden sculpture of a Black man's head carved by the owner of the land, a former slave. The carving is allegedly from a Hoodoo tradition used for protection and healing.

The former governor of Texas, Rick Perry, came under fire during his tenure because his family rented a hunting camp called "Niggerhead." The name was carved on a stone over the entrance to the hunting camp, but Perry claims his father had the stone painted over when he began renting the farm in 1983.

In 1963, the federal government ordered that the name, "nigger" be replaced on all maps and geographic terms with the word, "negro." The fact that the federal government had to order the word to be removed and replaced demonstrates just how often the n-word was used on maps and in geographical naming. These maps, similar to the one my father showed me demarcating his father's property lines, are a present and simultaneously past relic of how deeply entrenched racism was embedded in the very fibers of America.

I wonder how long those heads remained on those poles along the road Daddy took us on back in Roseboro, North Carolina. How many wagons and horses carrying children and families passed by those decaying men's heads, eyes, and ears, oblivious as they focused on their destinations? How many people walked along this road full of human stakes, guiding them along their journeys?

The decapitations would have taken place around or after 1831, after Rev. Nat Turner's infamous rebellion in Southampton, Virginia. My father was born in 1953. He shared the property map with me in 2022. Almost 200 years had passed before a story could be pieced together to connect the heads of the decapitated men, my father's memory, a county yearbook, and my personal research endeavors. Trying to write a story to connect 200 years of history is dizzying. Making sure the story is supported by factual evidence, exhausting. Being able to tell my father he was right and explain why he was right, exhilarating.

My experience of geographical place-making to validate my father's memories and more broadly the memories of my community is a personal labor of love. I followed the trail of "Negro Head Road" archives and internet data similarly to the way my father guided my siblings and me through the woods that day—slowly, carefully, and patiently. I offer you the same advice. If you choose to travel down memory and historical lanes: Move slowly. It will take time. Be careful. There is more than meets the eye. Be patient. Truth is often hidden in plain site.

I have always been under the impression that nothing of interest happened in my sleepy, rural, quiet, hometown of Roseboro. My father's old property map changed my mind forever. It also reminds me that as much as we think we know about history, there are still worlds, places, and people to be uncovered, acknowledged, and liberated. Do not forget to remember them.