This essay includes descriptions of anti-Black violence.

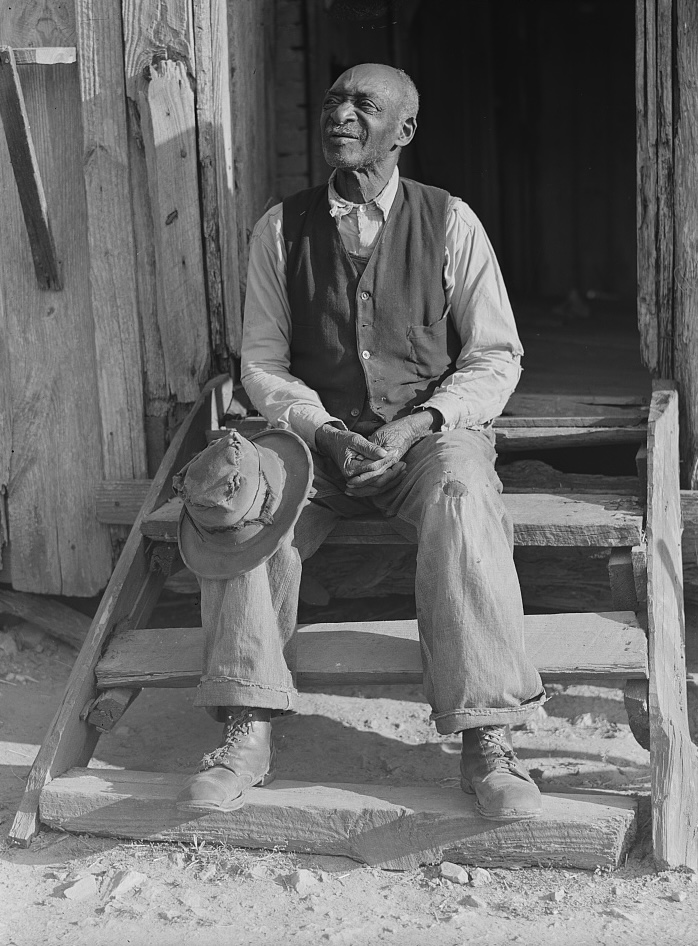

Pam Colby said she got goosebumps. Scattered across the New York cafe table where we sat were fragments from the life of her great-great-grandfather – a man she had never heard of. I had found many of the pieces during my research for a book about her ancestor's home, Greene County, Georgia. A newspaper article here, a congressional transcript there. And a pair of biographies that had long told the story of one of Georgia's first Black legislators. The first biography read: "ABRAM COLBY. [Colored member from Greene County.]"

Like the other Black representatives in the 1872 register, Abram Colby's redacted story floated among lengthy glowing accounts of his white legislative assembly peers. Colby's second biography, published in a county history book, described him as an ignorant drunk who insulted a lady and was thrown out of town, never to be seen again. These archival records are all that comprised the entire memory of Colby for generations, save for one other detail preserved by his congressional testimony: the Ku Klux Klan once beat him so severely that a doctor mistakenly declared him dead.

…a slave who inherited a plantation and had an audience with the president. A visionary who sought to lead an exodus of freedpeople out of the Deep South. An early Civil Rights leader who lived under the constant threat of white terrorism, yet remained faithful to his cause until his final breath.

In the different fragments, however, someone else's outline came to the fore: a slave who inherited a plantation and had an audience with the president. A visionary who sought to lead an exodus of freedpeople out of the Deep South. An early Civil Rights leader who lived under the constant threat of white terrorism, yet remained faithful to his cause until his final breath.

Pam Colby, whose daughter is an actress, quoted the musical Hamilton as she looked over the uncovered documents: "Who lives, who dies, who tells your story?"

In 1850, when John Colby passed away, the former New Englander had vast lands in Georgia and a mansion called "the Poplars" in his possession. As his white descendants prepared to inherit it all – as recalled in the memoir of his white granddaughter, Henrietta Sprague – they discovered a shocking wrinkle in his will. The Poplars and about 1,000 acres of surrounding land would be preserved for the use of Mary, an enslaved woman, and their children. Mary had given birth to several of John Colby's children, including Abram, when she was a teenager some 30 years prior. And so, while still enslaved, Abram Colby entered adulthood with de facto possession of a plantation in the Deep South.

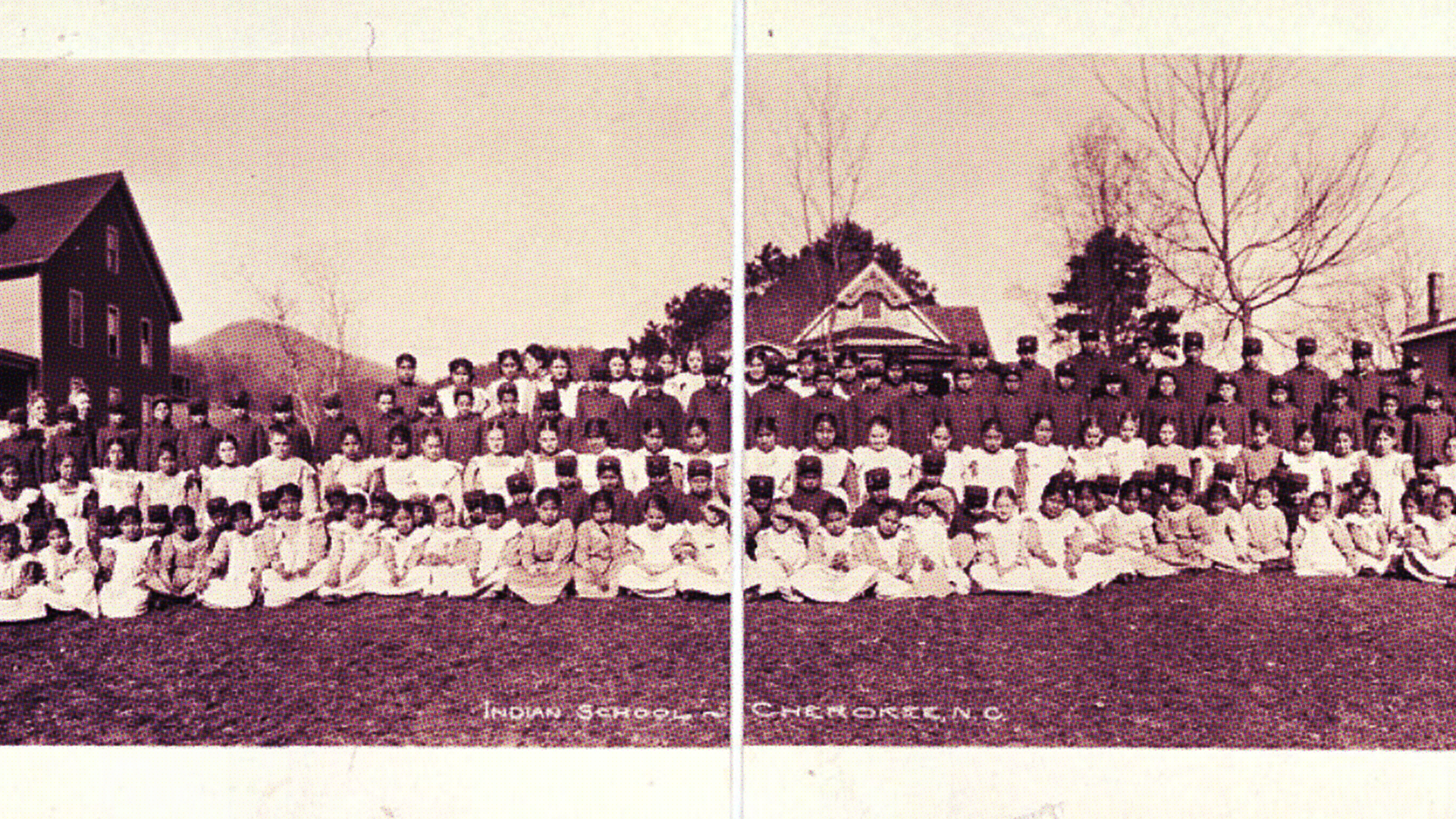

When the Civil War ended, Colby prepared to extend to others the slice of freedom he had come to know. He saw education as key, though he was illiterate, Colby ensured that his son, William, learned to read and write. With support from Union soldiers, Colby and other freedmen opened the "First Colored School" with a Black Army cook serving as its first teacher.

Acknowledgment as Denialism:

The Myth of Reparations in the US

Still, with no "40 acres and a mule," the severe postbellum racialized economic inequality forced freedpeople back onto their old plantations. Those who resisted the new order of labor exploitation were deemed vagrants or criminals and either jailed or carried back to work. "I do most solemnly declare in the presence of God and man," Colby said in a letter written on his behalf, "that I do not see the most distent [sic] shadow of right or Equal justice."

Hope appeared from far away. The 1866 Southern Homestead Act declared that Americans who had not supported the Confederacy could claim 80 acres of federal land in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Colby and a coalition of freedmen wrote that they and between 1,000-1,200 other freedmen of Greene County, Georgia, wanted their share.

Those who resisted the new order of labor exploitation were deemed vagrants or criminals and either jailed or carried back to work.

Backed by the support of the Freedmen's Bureau, Colby and two other freedmen rode on horseback between Arkansas' western River Valley and the rugged ridges of the Ouachita Mountains farther south in pursuit of the homestead land opportunity. Colby told the Memphis Daily Post that he sought good land regardless of its distance to rivers or trains; the freed colony would build tracks themselves if need be.

But when Abram Colby and the freedmen arrived in Arkansas, they encountered a dismal scene. Bands of rebels assailed the countryside while locals battled starvation. Even the office where Colby needed to apply for land had closed. Letters regarding his case circulated from Arkansas to D.C. and back, but the same government that failed to deliver on the promise of "40 acres and a mule" had now failed to grant him a single acre in Arkansas. Colby returned home to Georgia empty-handed.

Undeterred by this misfortune, Colby changed tactics. He decided to take a seat in the very government that had failed him. To the horror of Georgia's old ruling class planter elites, the newly enfranchised electorate of freedmen carried Colby to a landslide electoral victory in the 1868 state congressional election. Colby traveled to Atlanta with his son, who read and wrote on his father's behalf. The two appeared alongside Black and white Republicans, who together constituted the state congressional majority. Note that the Republican Party played the main role in promoting Black civil rights until the Great Depression and the Civil Rights Movement, when the two major parties switched on racial issues.

While the Klan terrorized Black voters during the election of 1868, decimating the Republican vote by 90 percent in the counties to the north and south of Greene County—Colby and his supporters defiantly marched en masse to the polls.

One of these white Republicans was Robert McWhorter, the second representative from Greene County and the House speaker. Though a former enslaver, state representative, and major in the Confederate Army, McWhorter had enraged local white residents with his friendliness toward Colby. When the House debated whether Black politicians could legally hold their seats, however, McWhorter suddenly excused himself. Speaker pro tem William Pierce Price, a member of the opposition, ruled that Black representatives could not vote on the matter. As Colby watched helplessly, the white representatives overwhelmingly voted to expel their Black colleagues. According to the Greene County newspaper, the absent speaker earned a nickname among the freedpeople: two-faced McWhorter.

Still, Colby continued his fight for racial justice beyond the statehouse. While the Klan terrorized Black voters during the election of 1868, decimating the Republican vote by 90 percent in the counties to the north and south of Greene County—Colby and his supporters defiantly marched en masse to the polls. In the presidential race, they successfully carried the county for Gen. Ulysses Grant, the Union army commander who broke the Confederacy.

Suspended from the legislature, Colby focused his efforts to undermine white supremacy through the "First Colored School," which he helped found in 1865. The school not only taught Black pupils valuable new skills but also challenged old beliefs. According to a soldier stationed in the county, Colby's white teacher from Rhode Island, R. H. Gladding, walked through town arm-in-arm with freedwomen under a shared umbrella, blurring the county's sharp racial lines.

Suspended from the legislature, Colby focused his efforts to undermine white supremacy through the "First Colored School," which he helped found in 1865.

One night, according to Gladding, masked Klansmen dragged his half-dressed landlord outside at gunpoint and demanded Gladding's location. But according to a freed boy, Colby's brother had preemptively escorted the teacher to their plantation. Colby relayed the story to the military authorities, according to Reconstruction Governor Rufus Bullock, who ordered Lt. George Hoyt and his company to protect the educator.

Few acts could have enraged the white Greene County residents quite like the return of federal troops and their occupation. In a retaliatory act to bring Colby's considerable influence to their side, a local merchant offered him $5,000 to switch to the Democratic Party. Colby refused: "I told them that I would not do it if they would give me all the county was worth."

What happened next comes from the testimony of Colby and Lt. Hoyt.

On the cold night of October 29, 1869, two days after Colby refused the bribe, dozens of Klansmen broke through Colby's door while he slept. Guns drawn, they seized him from his family. His young daughter begged the masked men not to take her father, but they pulled a gun on her, sending her into shock.

The mob marched Colby away, striking him as they went. They accused him of voting for the Republicans and bringing back the "Yankees." In such a small county, Colby recognized the voices under the masks and the boots on the men's feet.

"I will not tell you a lie," Colby said. "If there was an election to-morrow, I would vote the Radical ticket."

Forcing Colby to the ground, the men took turns beating their former representative with sticks and straps with buckles. The Klansmen asked, "Do you think you will ever vote another damned Radical ticket?" referring to the wing of the Republican party that supported the freedpeople. "I will not tell you a lie," Colby said. "If there was an election to-morrow, I would vote the Radical ticket." Colby asked the men to finish and kill him. As he began to appear lifeless under the blows, the town doctor felt Colby's bloodied wrist and found no pulse.

Colby's brother found him the following day—back shredded, hand paralyzed, cuts running from his neck down to his legs—but alive. For days following the attack, Colby could not rise from bed, and after his recovery, he continued to walk with a limp. Still, what grieved him most was his daughter. Colby said she died from shock.

In the aftermath of the brutal attack, Gladding fled Greene County and three months later, Georgia's Reconstruction General Alfred Terry reinstated Colby and his Black colleagues to their seats. A wounded Colby tried desperately to ensure their safety. On a trip to Washington, D.C., he and his fellow Black legislators met with federal politicians to explain their plight. President Ulysses S. Grant agreed that they deserved protection, but Colby said many others expressed disbelief that conditions in the South could be so bad. Colby found similar reluctance back in Atlanta when his Black colleagues attempted to pass laws to protect civil rights and form a Black militia.

When Colby returned to Greene County seeking reelection, James Sanders, the father of one of the Klansmen who attacked him, ran for Colby's seat. According to county historian Thaddeus Rice, Sanders prevailed.

Rice had long defended Greene County's white elites, with his rose-colored history serving to legitimize their power. He wrote, "After Colby's defeat his drinking and insolence led to his 'Waterloo.' He insulted a lady on the streets of Greensboro and he was soundly thrashed and put on an out going train and told never to come back. No one ever saw him again." This version was written into the History of Greene County, Georgia and Tenants of the Almighty, Arthur Raper's sociological treatise. It appeared again in Oconee River: Tales to Tell, published by a local history teacher in 1995.

But there was a major problem with Rice's account: Colby won.

Indeed, the reelected legislator even found a ray of hope shining from Washington, D.C. An investigation into Klan violence in North Carolina had delivered harrowing stories to Capitol Hill. Congress gave President Grant the ability to suspend habeas corpus and destroy the Klan. The House and Senate also launched an investigation into Klan violence throughout the South, with Colby testifying before a committee meeting in Atlanta.

Despite this, Colby's position remained precarious. The Klan maintained their vendetta against him back home. The Republican majority had disappeared from the statehouse, as had Governor Bullock, who fled impeachment and felony charges from the new Democratic majority. Former Confederate Colonel James Smith soon took Bullock's place.

Unpacking the KKK's Role in Corruption

A forgotten coup in the American heartland echoes Trump

In the election of 1872, Colby's party made a desperate attempt at reversing course. Former Georgia Supreme Court Justice Dawson Walker who campaigned to unseat Smith, kicked off a speaking tour in one of the state's last surviving bastions of Black political power: Greene County.

Two days before Walker's speech, Colby slipped onboard the night train from Atlanta to Greensboro, Georgia. He never made it home.

Augusta's Daily Chronicle & Sentinel reported:

DEATH ON THE CARS – Abe Colby, the notorious Radical colored Representative from Greene County in the last Legislature, died on the cars between Atlanta and Greenesboro Tuesday night. One by one the flowers fall.

Walker's bid faced annihilation across the state, but in Greene County, the freedmen marched en masse to the polls once more. The county returns read, Walker: 984, Smith: 873. Jack Heard, another freedman, won his race to replace the late Colby in the legislature.

Still, the fire Colby had long stoked began to flicker. In the years that followed, his family departed from Greene County, the Black vote collapsed, and to this day, Heard is the last Black politician to ever hold Colby's seat.

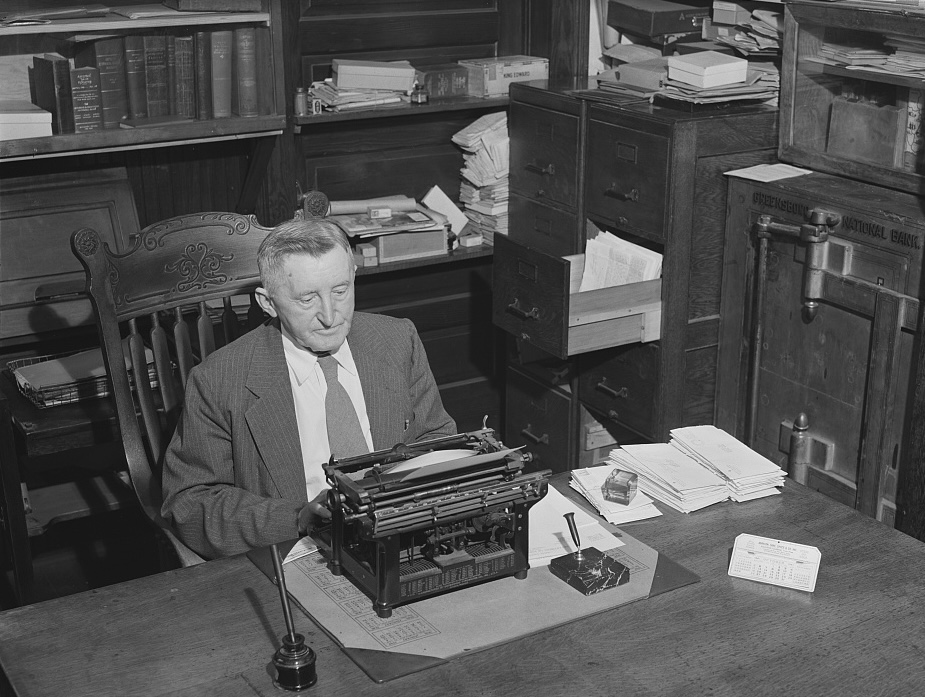

In 1990, Jonathan Bryant could barely find a single person who had heard of Colby. The University of Georgia Ph.D. student had started digging up the truth for his history dissertation. Bryant's book, How Curious a Land, cut strongly against the history repeated in the county for generations.

Other researchers continued to unearth the truth. I joined Tara Coile, a county librarian, in tracking down the rest of the story told here. Macky Alston, a documentary filmmaker, found surviving members of the Colby family, none of whom had ever heard of their ancestor.

The sun poked out between the clouds above the old Greensboro, Georgia, courthouse one fall afternoon. Over a century and a half prior, Colby had marched with the freedmen by its great white columns to cast their ballots. The ultimate victor of those contests lies outside: a Confederate soldier stands atop a pedestal, his stone eyes staring forever forward. Just two years after his guard began in 1898, white county voters disenfranchised their Black neighbors by creating a white primary. The statue purports to honor "the brave who fell defending the right of local self-government." But the memory of Colby's battle for his right to local self-government is nowhere to be seen.

His vision for the future was erased too. After the Civil War, Colby fought for a Black community apart from the old plantation system. While some Black-owned businesses do succeed today, the central economic gravity of the county lies with its gated communities, including Reynolds Lake Oconee, formerly known as Reynolds Plantation. Scores of Black, Hispanic, and white locals find work in service to these almost uniformly-white neighborhoods, often for paltry wages. Meanwhile, the public school system that Colby helped to establish remains wracked by segregation and seismic performance gaps. Everywhere, a Colby-shaped hole remains. But thanks to his erasure, few know how different it all could have been.

One of the few to know his story is Mamie Hillman. A Black Greene County local, Hillman had felt no connection to the county history written by Rice. In the pieces of Colby's story that Bryant uncovered, Hillman found that connection. And so began her decades-long journey to unearth the truth in her community, which culminated in opening the Greene County African American Museum in 2021. When asked why so much of this history is buried, she said, "I believe they did not publicly acknowledge it because they knew the power of it."

On that breezy fall day at the courthouse, about a dozen people held candles with Hillman. She had organized a candlelight vigil along with a memorial dinner that evening in honor of Colby and his fellow expelled Black legislators. "We're here to honor and celebrate and acknowledge those 33 beloved men," she said, "who only wanted an opportunity to serve their community and its people."

"Their lives and the lives of their family were never the same," said Hillman. To her right stood Pam Colby, who had crossed the country to be present for the event. Her family was never the same. Just nine days after Abram Colby's passing, his plantation was seized and sold. The family left Greene County and eventually moved to Gary, Indiana, where Abram's grandson worked in a sheet mill far from his grandfather's plantation.

"When we honor them," Hillman said of Abram Colby and his fellow expelled legislators, "we honor the best of ourselves." She then asked to close with a prayer as those present carefully guarded their flickering flames from the wind.