A gentle, driving rain pushed the modest rally underneath an overhang of city hall in Greensboro, North Carolina, where a couple dozen people had assembled to celebrate the formal announcement of a municipal workers union back on Jan.17. Chants echoed off the building's brutalist architecture as supporters and union members followed the call-and-response of UE 150's only statewide organizer, a lanky grad school dropout named Dante Strobino.

"Workers want a union," he prompted. Attendees thundered: "Organize the South!"

"Workers want a voice."

"Organize the South!"

Moments later, a city sanitation worker stepped in front of a scrum of reporters.

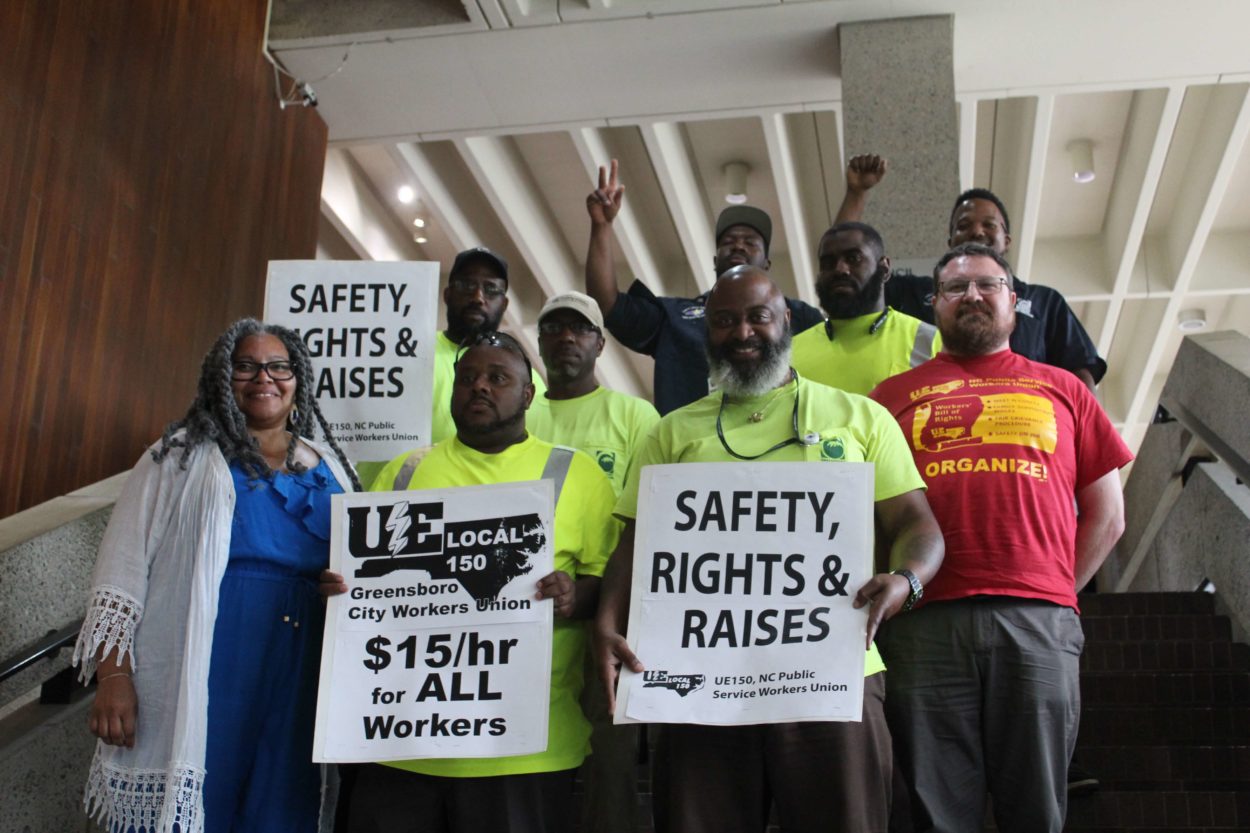

"I'm Charles French, the president of the Greensboro City Workers Union," he opened. "We are here to speak with city council to voice some concerns, to speak with them, and make our voice known to city council."

It had only been a couple months since French and other city employees had begun meeting with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America — or UE for short — at a local Bojangles. By the January rally, more than 60 workers had joined the unionization effort.

Like almost all of the union's members, French is Black. He sported a cleanly shaved head, and grey rims the bottom of his neck-length beard. Wearing a bright yellow, long-sleeved city shirt, the former long-distance trucker explained that employees had found common ground on a variety of grievances including pay, working conditions and understaffing.

"We've spoken with people with high authority, but we've felt like they never really heard us, so we've come together to try and form a union, to speak together with our leaders to see if we can't get something resolved," French told the press. "We're the only ones who don't have a union. Police and fire have their unions, so we want to have a voice as well."

Over the next few months, the union would grow considerably in size, winning the ability for members to have union dues deducted directly from payroll and pushing the city council for higher wages that members argue they don't just need, but that they also deserve.

Greensboro isn't the union's only outpost in the state. And if rank-and-file employees have their say, the city won't be the last. It's part of a surge of public-sector union activity that — although somewhat new and still relatively small — is historic, given that it has gained a foothold in one of the nation's most anti-union states. And in union member Arthur Erickson's eyes, the Trump era makes this kind of grassroots, predominantly Black labor organizing an imperative.

***

The groundswell in Greensboro is part of a statewide campaign for UE 150, the municipal workers local in North Carolina. Strobino — who dropped out of graduate school at NC State to become a field organizer for the union — said they realized that the union couldn't win in just one city.

Sitting in a Greensboro coffeeshop recently, Strobino said that North Carolina cities often compare themselves to each other in terms of policies and wages, making it natural to link struggles in one city to another. He shuffled through a small stack of fliers that he's used to leaflet outside Greensboro city facilities, including a large broadside that extols UE 150's successful fight for pay raises and salary adjustments in Charlotte. The NC Public Service Workers Union — as it's also known — boasts chapters in six cities across the state. Most chapters are in big cities, but UE 150 also has an outpost in the smaller eastern North Carolina community of Rocky Mount. That's no accident.

Rocky Mount is the birthplace of an organization called Black Workers For Justice, a group that began in 1982 "out of a struggle led by Black women workers at a K-Mart store," the organization's website explains. Black Workers For Justice believes in "self organization" of Black workers, the website states, adding that it is part of a movement "for Black liberation and workers' power."

Jim Wrenn, the statewide secretary/treasurer of UE 150 and a worker at Cummins Rocky Mount Engine Plant, explained that Black Workers For Justice launched organizing initiatives at several plants in the area at the end of the 1980s and then later joined in a fight alongside housekeepers for the UNC school system in 1996. Next the union organized workers at state mental hospital. It then expanded to municipal employees when an existing city workers union in Durham — which was originally part of the American Federation of State, County & Municipal Employees union — decided to formally affiliate with UE 150, Wrenn said. From there, efforts to unite municipal employees would spread across the state to cities such as Raleigh in the mid 2000s before eventually finding a foothold in Greensboro.

Yet despite this growing list of campaigns, and the other organizing history Wrenn easily rattles off, North Carolina is not union country. Quite the opposite.

***

North Carolina has the second lowest unionization rate in the country, according to 2017 stats from the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics. A mere three percent of workers in the Old North State belong to a union; only South Carolina has a lower rate, at 2.1 percent. The Carolinas recently traded places for the title, with North Carolina ranking lowest at 1.9 percent in early 2015, the Charlotte Observer reported at the time.

Neighboring Southern states Virginia and Tennessee aren't much higher (both at 5.4 percent), and only four percent of workers in Georgia belong to a union. The South isn't uniform — the number jumps to 10.2 percent in Alabama — but most Southern states are only a couple clicks above North Carolina.

The low rates of unionization in the South are nothing new. Most states have made it a policy to oppose unions. North Carolina sent National Guardsmen to break up strikes in the 1920s. The state later passed an anti-union, right-to-work law in 1947 and, four years later, voted down an attempt to pass the state's first minimum wage and overtime laws, according to a different Observer article. States like North Carolina used their lack of unionism to advertise a cheaper cost of labor to outside industries, which attracted companies like textile mills into relocating from more unionized states in the North. Union supporters argued that this was a losing strategy long-term, as many of those same industries moved overseas by the early 1970s, again on the hunt for cheaper labor.

But that doesn't mean there isn't a long tradition of union organizing in North Carolina, or in Greensboro specifically.

Home to two historically Black colleges, Greensboro is famous for being the catalyst of the sit-in movement during the civil rights era. The city used to be beholden to the textile industry that dominated the region, and so it's no surprise that the mills were where a coalition of Black and white labor organizers turned their attention in the 1970s.

A group called the Workers Viewpoint Organization — later renamed the Communist Workers Party — didn't just receive pushback from management when it tried to organize the textile mills. It also ran into fierce opposition from the KKK. On Nov. 3, 1979, the KKK united with a group of neo-Nazis to attack an anti-Klan rally in east Greensboro, killing five people active in the state's labor movement.

During the assault — which later became known as the Greensboro Massacre — several others were injured, including Wrenn, the future UE 150 secretary/treasurer.

Rev. Nelson Johnson, a Black activist who'd been a fixture in various causes in the city, had led the anti-Klan rally. He, too, was injured during the massacre. Johnson would later become a reverend, and today he's at the forefront of the city's movement for police accountability. At the Jan. 17 Greensboro City Council meeting when the workers announced their union, Johnson was one of three black pastors to speak on their behalf.

"Unions have done more to help poor, working people than any other entity that I know," Johnson said as he stood before council. "It just makes sense for people to join together to work for their own best interest."

***

The Greensboro City Workers Union hasn't run into the sort of fierce opposition one might expect from a state with such a strong anti-union history. Democrats overwhelmingly control the Greensboro City Council, but their public response has largely been tepid.

Several Democrats on council are quick to emphasize their moderate credentials, including Black corporate lawyer Justin Outling. Many residents consider white Councilman Mike Barber to be a Democrat in name only. Democratic Mayor Nancy Vaughan, who's made a name for herself as a progressive on select issues, is a former Republican.

Instead of expressing outright support for the union, council members who have spoken publicly about its formation have opted to focus on the union's grievances around pay in particular. The Greensboro council had previously voted to bring most of its workers up to $15 an hour by 2020 with benchmarks along the way, but union members said the process fell behind schedule and left certain groups of workers behind.

That caught some of the council members' attention, including that of Mayor Pro Tem Yvonne Johnson — the city's first Black mayor, who served in the role from 2007-2009 and who was active in the Greensboro sit-in movement as a college student. Led by Johnson, a few of them pushed City Manager Jim Westmoreland to address lagging pay. Jamal Fox, a Black councilman in his late twenties representing east Greensboro, said that the city's employees are its best assets, adding that he wants to give employees a raise.

Vaughan, who is white and one of council's longest serving members, also seemed impatient about the city's slow implementation of wage increases, enough so that the union claimed it as a victory in a subsequent flier.

"Mayor Nancy Vaughan voiced support for workers' efforts, and particularly expressed frustration to the city manager, Jim Westmoreland, who has stalled on raising the floor wages since city council passed a resolution in August 2015 to raise the minimum wage of city employees to $15 per hour by 2020," the handout declared.

But Vaughan and others on council have stopped short of explicitly expressing support for the union itself. If anything, they've spoken predominantly in support of wage increases that they'd voted for more than a year before the union formed. While some council and union members may align on wanting a timelier implementation of the city's climb towards $15, it's still unclear exactly where all of the council members stand. They're staking out cautious and mildly supportive ground for the municipal employees, and while nobody on council has expressed active opposition to the union, only two members would later oppose the city budget because it ignored one of the union's primary grievances around pay.

***

The union is still in its early stages. But a couple months after its kickoff in January, Strobino said "a couple hundred" workers were involved, although he didn't put a specific number on membership.

Behind the scenes, the union has maneuvered for dues check off, allowing members to pay directly towards UE 150 from their paychecks. Flanked by about a dozen of the union's leaders, chapter President Charles French returned to the Greensboro City Council meeting on June 6 to thank the city for its progress and to push for raises.

As part of the annual budget being discussed that day, the council was weighing a three-percent raise for workers like French while considering a 7.5-percent pay raise for public safety employees proposed by Councilman Mike Barber. At a subsequent council meeting, the body approved a budget featuring Barber's proposal, with Black council members Sharon Hightower and Jamal Fox dissenting because of the disparate raises.

To employees like Chris Yancey, a Black water resources employee who started working for the city in 2010 when he was 24, the idea of two-tiered raises feels like "a slap in the face." Yancey — who attended the June 6 meeting wearing his dirty work boots, scuffed-up blue Dickies and a Pittsburgh Steelers lanyard around his neck — joined the union early on because he said he believes that there "ain't no need in complaining if you're doing nothing to resolve it."

Like his fellow workers, Yancey is also concerned about understaffing.

"The city is growing every day, but the workforce ain't," he said, adding that work crews are often understaffed. Departments like his remain largely invisible compared to public safety. But that doesn't mean his job isn't important or dangerous, he said, describing the risks of being in a hole and digging certain kinds of dirt.

Given time to talk about their jobs, workers like Yancey can rattle off a litany of issues they're facing. That's part of the reason the union is quietly writing a worker's bill of rights which will outline policies on raises, training, job protection, a grievance procedure, staffing levels, and more.

Publicly, the union remains largely in the awareness-raising stage and will continue to organize for higher pay and adequate staffing. The union's primary focus, however, is still on recruitment.

Yancey is confident the union will grow — regardless of the disparate raises — because he said there are hundreds of other Greensboro employees with similar problems. And Yancey said he's bullish on the union's future in part because of the strength of the statewide NC Public Service Workers Union, which acts as an inspiration and a resource.

"This is bigger than just us," he said, taking a moment to sit on a flight of steps outside city hall after the union made its case to council on June 6. "This is y'all, too. We're not trying to leave nobody out."